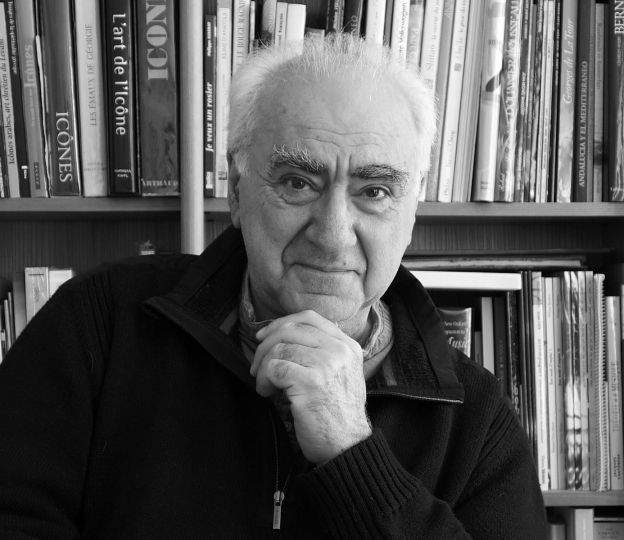

Farewell, Lewis, you were an incredible man.

Jean-Jacques Naudet

What was Southern California like when you were a kid?

It was a different California, with six million people, instead of 40 million; provincial to a degree almost unbelievable to anyone who’s been there today. It was not cosmopolitan California. Most people were White; most of them were from the Midwest. The Hispanics were from the northern provinces of Mexico; the African Americans, as they are now called, were from the American South. Los Angeles today has over 200 languages in the school system—Blacks could be from Sudan, Whites could be Russian, Hispanics could be from Central America. I think it’s now the most cosmopolitan city in the western hemisphere. The other such city is Toronto, where they seem to get along pretty well. Los Angeles tends to have drive-by shootings.

Where were you living?

In a small part of Newport Beach, Corona del Mar, which was about 75 km south of LA civic center, on the water. It was different from other small towns in that it had a natural small-boat harbor; the closest to LA, which is why the movie stars who fancied yachting lived there—Errol Flynn, John Wayne.

Did you have a nice house?

No. There weren’t any. Well, there was one: the Lovell beach house, built in the Twenties on the Balboa section by Rudolf Schindler.

You told me once that when you were 12 you wanted to have a work at MoMA. What shocked me was that you even knew about that museum and about art.

When I was eleven my parents gave me a camera and I started taking pictures. I was fascinated by photography. Then, at 12, I got a Rolleiflex. I read the literature, which there wasn’t much to speak of. There were no art magazines. I wouldn’t have seen them anyway. I think there was Art News, from New York, run by Thomas Hess. Photography magazines were like Popular Mechanics, more technical than aesthetic. Still, from reading camera magazines I learned about Robert Frank’s The Americans and about Edward Weston—who I wanted to be. I thought Weston was doing the best thing you could do with photography. But photography wasn’t so much an art.

How did you know about art—it must have seemed very far away?

Yes, very far away. There wasn’t much in the West Coast. Los Angeles as an art center is very recent. But if you knew about Weston, you learned that he had a retrospective at MoMA. There was so little written about photography that it was easy to learn such things.

Did you develop your own pictures?

I did, and it was difficult

I thought you worked at a photography shop?

I did. I worked at William Current’s shop. Much later he was in MoMA’s collection. I learned more from him than from anyone. My father had died, when I was 12, and I was looking, I guess, for a mentor.

Did you have brothers and sisters?

A No.

So you were filling up your own space

I was trying too. There was something odd about the way families lived. Everything was conformist. Everyone was a Republican, everyone in Orange County, anyway.

Did you get a car when you were 16?

Fifteen and a half, because in California there was something called a Learner’s Permit, which lets you drive, so long as you are accompanied by a licensed California driver.

What was your first car?

A 1959 Porsche 1600, which I wrecked when I was 16. The next one was also a Porsche. I wrecked it even faster.

What was high school like?

I was enrolled in high school. I wasn’t very good. I was bored to death. One comment about me read: “If you just considered the days Mr. Baltz was present, he did rather well.” I was absent, legally or illegally, over half the time. I wanted to study about art and to stay home and read.

Did you learn about art?

I read all those cheap Skira and Abrams books with the tipped-in illustrations. On Monday nights there was an open-door walkabout at the gallery district in LA, so I started seeing galleries. I wanted to be an artist. Most people don’t know what they want to do with their lives. I had an absolutely clear idea: I wanted to work in the medium of photography; I didn’t want to be a painter or sculptor—or work in advertising, fashion, or make war pictures or documentary photography. I also wanted to live in a beautiful place and have beautiful women come to visit at all hours of the day or night.

Did you shoot only in black and white or also in color?

First in color, and then I realized that every photograph I admired was in black and white, because all artistic photographs were in black and white and remained so until the mid-Seventies.

What photographers interested you?

At about 16 or 17, I wanted to meet people like Weston, Wynn Bullock. I’d even call them up and ask if I could meet them.

Did you meet artists?

Some years later, when I was about 18, I met the painter, John McLaughlin, who was in his seventies. I met him through William Current. Bill photographed his work as a favor, and wasn’t that fond of it. Bill’s taste was not minimalist; he thought McLaughlin didn’t use the possibilities of painting—the hand, color. His idea of a great painting would probably be Matisse or Kandinsky, which you can’t argue with. Bill had a McLaughlin painting, given to him for photographing the work. He had the painting in the camera shop, which he designed in the neoplastic in style—white, clean, rectangular, primary colors—which no one responded to in one way or another. Then when Bill left Laguna—a bad businessman, though he did get a Guggenheim and then moved to Santa Fe, but before leaving he asked me if I wanted to buy the painting. It was a ridiculously low price. But he insisted on the price, asking me, “Do you want it or not?” So I paid and got it.

What did you think of McLaughlin’s paintings?

I thought they were sublimely beautiful. I thought they did what a painting could do—with extremely limited means he could make something seriously contemplative and moving. I thought they were brilliant…. McLaughlin was a Japanese speaker, an authority on Japanese art, he’d worked in Japan as part of the American occupation, but he never studied painting, and so it’s hard to find an undamaged McLaughlin painting. He was as careful as he knew how to be, but, as a result, the paintings were often not in good shape. I had a friend doing a Masters Thesis on McLaughlin and I asked that friend if he could arrange that I meet him, which he did, and McLaughlin said to bring the painting by for him to look at. McLaughlin looked very much like an English gentleman, sort of like Walthur König. He and his wife invited me in. I thought I’d just drop it off. He told me to check back in a couple of weeks, but then he needed another month, because he completely repainted the painting, which is on a kind of cardboard, which is already problematical. I took back the painting, and he refused compensation. I felt guilty for taking up his time, but I realized later he was delighted, because no one saw him or called on him.

Was he a recognized artist?

He’d had his picture in Life magazine, and was in a show at the LA County Museum—five California abstract artists. He showed at an LA gallery. But it was a smaller world.

Were McLaughlin’s paintings anything like other contemporary art you’d seen?

Well, it was like California Hard Edge, but I didn’t know that then.

What did you do after you finished high school?

In 1963-64 I went to a community college in Carmel, on the Monterey Peninsula, because I couldn’t get in anywhere better. But it was near to where Weston had lived. I studied as much art history as I could, which wasn’t a lot, and took courses in photography, which didn’t help much. I stated out as a business major because the Vietnam War was on and I thought that would look more serious. I still believed in classical photography. I went out to Point Lobos to shoot, but after a while I realized I lived in a different world, so I started looking around my world. I loved Weston—still do—but my world was different. I wanted to find something of my own time, something that had authenticity to me.

What did you photograph?

Back then I shot in nature, but I later destroyed all that work. Then I started what became the Prototypes when I was still in community college, but on my way to the San Francisco Art institute, which I went to up until 1966-1967, the summer of love.

Did you change your way of dress?

I never got the style right, and the movement didn’t hold much interest for me. I didn’t react well to the drugs they liked. I liked to drink; I liked amphetamines; cocaine hadn’t been invented for Americans yet. I hated smoking pot. I tried. And I’m not much into music. I was more of a Beatnik—literature and alcohol. But you had to learn the language and social codes. You had to know your astrological rising sign. If you didn’t learn them, you had no one to talk to, no sexual partners. When I was 18, 19, 20 my friends and I considered Naked Lunch America’s greatest work of literature. We could all quote it at length. Years later I contacted Grove Press to buy the film rights, even though I suppose the book is not filmable, which Cronenburg proved. Burroughs was a really bad boy.

He came from enough money that he could give himself permission to be bad, unlike Ginsberg, who always remained a nice person. Those people—the Beats—largely defined us. What were you reading—and always reading as you do still?

Norman O. Brown, Borges, Pynchon: I was always reading.

You were 22 in 1967. What was the San Francisco Art Academy like?

At its absolute bottom. It was a new building, which wasn’t finished, so it was a building site. No one came to class, even the professors. I did two years, finished my undergraduate work, cum laude, though I spent a total of 21 hours on campus. I was living across the bay in Sausalito, taking pictures, developing them at my own house. But they’d also opened a graduate program and couldn’t refuse their graduates into it, so I blackmailed them.

Did you make good prints back then?

The ones in my retrospectives are all from then.

You photographed a 1957 Chevy.

I photographed a ’57 Bel Air. It was the most elegant car of the era—it had everything.

That was my first car; it cost $365. You first called them the Highway Series—the title reminds me of Dylan or the Beat Generation. Were you listening to music?

Not like you did. We all listened to folk music, protest music, Dylan. I thought that what happens in America happens along the edge of the highway.

Did you feel different?

Well, for a long time I didn’t see anyone who was interested in what I was interested in. When I was in upper-division art school in San Francisco I was always taking heat for not taking cool pictures of rock stars, something part of the hippie world. Remember the New York/New Wave show?

Yeah: Queens, 1981, at PS 1. I’d arrived in New York the year before.

Yeah: a good photograph was a shot of Blondie. But my pictures were well enough made that people couldn’t complain.

Let’s talk gear. You mentioned Edward Weston, who seems to have had a similar personality as you—sensitive, quiet, solitary, serious, uncompromising, not particularly materialistic, but he used a large format camera.

Weston made contact prints using an 8 x10-inch view camera, probably because the materials and objects up until the 1950s weren’t very good. He couldn’t have made a Gursky-sized print. But 8 x 10 (20 x 25 cm) is big enough to see an image. Otherwise, if you introduced a lens system, at another generation you get a degradation, and then you had to use a different paper, to make a bigger picture, say 30 x 40cm or 50 x 60cm, which might not have been worth it. The paper that you printed contact prints on was very good and had a very long, with very subtle, tonal range, which the larger paper didn’t have then. It also took a long time to develop, say, when you turned a 100-watt light on the paper from about a foot away and left it on for minutes.

What did you shoot with?

I used a Rolleiflex or a Leica. Everything I shot until about 1980 was simple 35mm film. But I had help in finding very sharp lenses. There were stores around San Jose where you could buy Leica lenses. They’d be in a cardboard box, and cost $12.50 each. William Current told me to look carefully at them and pick a couple out and test them out.

What size picture did you make?

Each one was roughly 7 x 9 inches (18 x 23 cm). The quality of paper was much better than it is now. There was a lot more silver in it. I used Agfa paper and 35mm microfilm, which wasn’t complicated, but if you developed it for continuous tone it failed every lens you put it with, hazing and fading at corners. It had problems. If the average film was ASA 125, it was ASA 6, which means you had to use it on a tripod, outdoors, on a sunny day. Unless you wanted to use your lens wide open at F2, but then you discovered that your lenses aren’t sharp enough, because the optics at the time weren’t that good, at least until F5.6 or -8. There’s also a very short developing time, and to do this you have to be very precise. Film rolls that developed for, say, 20 minutes, you can shake a bit in the can to make the negative, before developing the picture. But this takes a minute or two, so any mistake accrues. When it did work, it had no latitude; you took the correct exposure to make the picture. With this you would take five exposures, one spot on, one over, one under, two over, two under, and one would be printable, so it was tricky. I did it to get the sharpness.

Did you learn all this by yourself?

I never really learned all the techniques of photography, such as developing film. So I had bad negatives for one reason or another, yet I wanted perfect prints, which is very time consuming.

Weston photographed nudes, still-lifes, and landscape pictures. Everything was a kind of positive, beautiful image.

Weston was the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. And he made a book called California and the West, which was 64 images made in California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon, and they’re the most beautiful and the most straightforward of his images — sometimes almost anti-compositional, sometimes leaving elements in a picture, say, a sign in the Sonora desert, a coffee cup. Most people think of Weston as more romantic than that.

But you take almost the opposite view, starting with the Highway Series, or Prototypes, as you later called them. OK, a beautiful 1957 Chevy leans toward an aesthetic object, but the majority of your subjects are not beautiful subjects, though each print is a well-made, maybe even a beautiful object. I mean, beautiful things are basically women and landscapes, and both imply some kind of relationship to security and safety, with women embodying culture and the landscape representing, at best, nurture or a search for safe haven against wild animals and what Samuel Beckett called the attacks of dogs and marauders.

Things can also be beautiful for their extra-visual qualities, which really doesn’t involve anything other than the eye. What a picture can eroticize is a different level of intelligence, which is erotic. Look at a physically crafted porn star and how sexless they end up looking.

But Weston, or even Ansel Adams or Robert Adams, gives you something like comfort food.

Well, Ansel Adams does because he’s not a very good photographer; he’s more of a popularizer, a fundraiser, a businessman; he wasn’t an artist. He made postcard pictures. But Weston—unlike Ansel Adams—was trying to be a contemporary artist. He corresponded with Kandinsky. Weston realized 19th century landscape ideals contemporaneously.

But you read something entirely different in the landscape.

I was 22, rebellious, and against society and the vulgarity of our country. I remember when I was seven or eight, walking around our seaside town, most of it looked like the desert with new houses. I thought the whole world couldn’t be this ugly, cold, and alienating. Probably all Californians my age and older feel like they’re the same age as the city they grew up in. I think Sartre wrote that American cities are straight lines and the citizens are older than the cities. It makes you feel meaningless. In European cities there are traces, even monuments, to human effort and persistence. Places like Los Angeles or Las Vegas make you feel like you could disappear overnight.

Americans grew up with newness. Maybe Weston was photographing the end of the frontier.

Everything we grew up in turned out to be the end of a frontier. I saw a world that was being shoved down my throat, and I thought by putting up a mirror to it I could show it to itself.

Did you have an idea of a better world?

Well, Europe is better.

When you were taking those pictures were you simply looking for subjects? Did they relate to each other?

I was just shooting images, later they started to relate to each other.

How did the “Highway” pictures evolve into the Prototypes series?

I was looking for subjects that would sustain a single body of work. I found interesting things in a few photographs, but not enough to make, say, 50. Sometime later I needed to call them something. So when it seemed that I might show them, someone, I can’t remember who it was, asked for a name and the word prototype came into my head and I said call them that. Actually I misremembered a title that I actually wanted to reference. Which was from an exhibition Joseph Kosuth had made at the Kunsthalle Bern, which included four little, very beautiful, badly printed books. I was also working on The Tract Houses, which I would eventually show.

Where were you going to show them?

At Castelli Gallery.

You went from zero to the Leo Castelli Gallery? How did that happen?

A guy named Hal Glicksman was the museum director at Pomona College, where I was studying in 1970-71 — I studied art, but as a photographer. I got in by showing what I’d done of the Prototypes, which hadn’t yet had a name. The graduate school was strange because it didn’t have its own faculty. You studied with various undergraduate teachers and do more so you got graduate credit. Pomona was interesting. Chris Burden went there. Hal looked at the work and wanted to show it in the gallery in the coming fall. He said he also had a friend whom he thought would enjoy seeing them. I was happy about that. It turned out to be Irving Blum, an already well-known art dealer who looked like a straight version of Cary Grant. He said they were “marvelous,” that they had a “classic beauty.” Irving called the Pasadena Art Museum to get them to show the work. The photography curator looked at them, and was nice, but didn’t say anything about wanting to show them. Irving was pissed as hell. I was apologetic, embarrassed. Irving said the guy’s an idiot and no wonder the museum is in trouble. He asked me if I went to New York. I said, not so often—I’d never been. He said October’s a good time. I’ll give you names of friends of mine. So I went in October, and I met Henry Geldzahler, who was working at the Metropolitan. I met the head of Aperture magazine. I met Philip Johnson, whose partner had a gallery, and loved the work but didn’t have an opening available to show them. He said I should see Leo Castelli, which never quite occurred to me. He set up an appointment for the following week. I was staying at a hotel, on 55th Street, which I hated. But I stayed and went to the Leo Castelli Gallery, then still uptown, on 79th Street. He hadn’t opened downtown. He was busy and said to come back in an hour. I left a portfolio, The Tract Houses, in case he wanted to look at them. I went to the 79th Street bar and had a double cognac, and then another, and then I realized I was late. I was nervous as hell. I didn’t think anything would happen. No one had ever met Leo Castelli. I expected nothing. I figured I’d get months of dinner stories just from the visit. So, I ran back, and he’s about to leave. Someone is helping him on with his overcoat. I thought he would tear me apart for being late. And he says in his very hushed voice, “Congratulations, Mr Baltz. I’m sorry I have to take a flight for Europe and I’m going to be late if I don’t leave now. But these are wonderful pieces and I’d like to buy a set and exhibit them. You can work out the details with my wife and the gallery director.”

Wow! How many images were in a set? How much did you sell them for? How many in the edition?

I sold the set for $1000 dollars, 25 images. They still have them. I showed them working prints. It was only then that I had to print them and figure out the edition. We came up with 12, with no artist’s proofs. I hadn’t thought about that as yet. One set of theTract Houses went to Irving Blum, one to one of my professors, one to Hal Glicksman.

How had you come to make The Tract Houses? What did you want to say with them? What were you after?

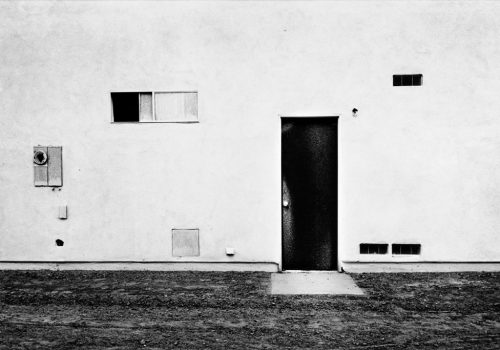

This was somewhere around the time when sculpture conquered the universe. Not object sculpture, but the idea that any object, or collection of objects, or spaces or acts could be seen sculpturally, no matter how commonplace. A pile of dirt could be read for its sculptural qualities; a pile of dirt on the back of a pick-up truck could be seen as a parody of kinetic sculpture. Everything could be recovered for this Weltanschauung, including painting (like early Frank Stella) and language (like by Lawrence Weiner or Joseph Kosuth). It seemed a triumph of the power of art. Art changed nothing, but by informing people’s perception of the phenomenal world it changed everything. The world was already in the condition of art, waiting to be noticed as such. As Robert Irwin famously said, ” I feel like a man sitting beside a river selling water.” I think that’s one of the reasons some or many of The Prototypes are jarring is because I use a high-art photographic technique to present views of nothing, that is, of no special interest per se. In my mind this was absurd, a metaphor of the condition.

You were different also from someone like Gary Winogrand. You had a different content from the photography of the time.

Gary always somehow showed himself, the photographer, with all those angles and hand-held images. A lot of people liked albums, family snapshots, but I never did. I liked the photographs in Real Estate office windows, which are technically correct and heartbreakingly empty. Let’s say that, with notable exception, I liked photographs made by cameras on a tripod.

Did those sentiments reflect your awareness of Minimalism, Conceptual Art, or even Land Art?

They were all closer to my sensibility, but I had a lot of sources—Bruce Nauman, Donald Judd, etc.

You were still in school.

Yes. I was in graduate school, working as a teaching assistant—actually teaching a class. One day when I was teaching a seminar class at Claremont College, Leo called the school. The receptionist got the call, and seemed to understand that it was a very important message, so she came and got me out of class, and saying, in front of everyone, “Excuse me, Mr Baltz, there’s a Mr Castelli on the line for you.” So I dismissed the class. Leo confirmed the show, exhibition dates, asked which image on the announcement.

Did your life transform?

Yes and no. Everybody hated me because I’d gotten all the goodies without paying any street dues. It was a brush with fame and fortune, because there was actually no market at all—none at all. We sold one set to a museum and that was it. I mean, back then, a Nauman drawing might sell for $125. Money was worth much more back then. Five dollars would fill your car’s gas tank.

Showing the Tract Houses at the Leo Castelli Gallery; did that in any way lead you to think differently about your life or work?

It was a powerful validation, but you have to realize, everybody hated my work. All the students I’d been to school with thought my work was too uptight. They wanted grainy pictures of Janis Joplin singing at a concert. What united them was being from a middle class family and not wanting to go in the family business. They were all sort of remittance men.

What were you?

My mother deserves a lot of credit, because she sold the family business while I was in college. She told me that I was about to go into the world and would find it very difficult and that I’d beat my head against walls and the idea of going back to Newport Beach to a safe business that’s making a lot of money might seem very tempting and she wanted to remove that temptation. She and my father had spent their lives in a mortuary and hated every minute, every minute.

Hadn’t your father been a musician?

He sure as hell wasn’t a mortician. That was the only medical business he could get into. So my mother didn’t want that business to be live and functioning when I was out in the job market. I couldn’t imagine doing that, but who could know what an unemployed person would do?

The Tract Houses and the Industrial Parks were bodies of work, in series.

They were invented to be that.

Did you ever sell them separately?

Not at first. I don’t remember when that changed, but collectors or galleries were buying portfolios and selling the photographs separately. They came in a box, but people would break it up to get more money.

Did you have to go along with that?

I became more accepting of that after the Industrial Parks because I had a book, and no matter what happened to the objects, I had the book. And one of the joys of multiples is that they can be put back together.

What came after the Tract Houses?

The New Industrial Parks at Irvine. They were from the area I drove through to go from where I lived in Laguna Beach to Claremont College where I taught. There was nothing in Irvine when I grew up, but things were going up fast, including a university. People like Chris Burden and Douglas Davis have studied at the new university, which had been built at Irvine. Barbara Rose was one of the visiting professors.

Joseph Kosuth once remarked that art making had become a form of noticing—rather than a form of copying or imitating, which is what most of art history is about. You seem to have made photographs about what you noticed was occurring around you.

This was the richest, most powerful country in the world, and what did it do? It made shopping malls, tract houses, industrial parks…

“The New Topographics” show at the Eastman House, in Rochester, New York, in January 1975, subtitled “the man-altered landscape”—how did that happen for you?

The second time I was in NY, which was for the show at Castelli Gallery, I went up to Rochester and showed them the work. This was Eastman’s private mansion. It was created sometime in the autumn of 1940, and had an enormous collection of historical photographs from France, just escaping Nazi occupation, which were to be given to a charitable cause. Beaumont Newhall, then the curator at MoMA, took it over, and under his direction they showed classic museum photography. But that had run its course by 1960 or so, and they hired some young curators—three of them, each in their early-to-mid 20s, each egging the other on to do an interesting show. One of them was Robert Sobieszek, who later became the curator at the LA County museum; one was William Jenkins, who later had a quiet teaching career in Arizona, as did Tom Barrow, who went to New Mexico. They said they loved my photographs and would like to buy a portfolio and to show it, which they did. My work also fed into something they’d been thinking about and working on — a lot of work that I hadn’t seen — which dealt with a spectrum of a single subject, the semi-built, highway landscapes, etc. “The New Topographics” show was a pretty good idea, and the exhibition was well done and well chosen. The only thing debated was why Ed Ruscha wasn’t in the show, and maybe that was because he was so much earlier and was making art book. Nevertheless, Ruscha was the presiding spirit over the whole show, because we all knew those books, and we all admired them.

What did you show?

I showed 18 pictures from the Industrial Parks.

Speaking of Ruscha, did you consider him a photographer in the same way as Weston—or even yourself? I mean, Ruscha’s pictures aren’t frontal and compositionally squared, and seem more concerned with the subject than the photographic image itself. I’m reminded of the quad of Ruscha photographs exhibited at Thomas Zander’s gallery in Cologne in 2012, along with your early works and some paintings by John McLaughlin— a brilliant exhibition. To me, Ruscha’s pictures weren’t so much great photographs as a brilliant series of images about a specific subject, LA apartments.

Well, let’s go back. If you’d read exactly what Clement Greenberg wrote about how art progresses through self-criticism, denial of extraneous factors, and constant refinement; if you believed it as an artist and acted on it, what you’d end up with is Conceptual Art, which Greenberg hated. He called it novelty art. Then you had to realize that Greenberg wasn’t playing in good faith. Whenever he said the word art, he meant painting. He was biased in terms of what painting could be. The most celebrated Greenbergian paintings, like Pollock or Newman’s, didn’t ultimately follow his precepts, either. Photography was the same. If you read what, say, Weston was writing in the1920s he talked about an industrial medium, reflective surfaces, contemporary subject matter—it’s a straighter line to Ruscha’s 26 Gas Stations than it would ever be to Ansel Adam’s pictures of Yosemite and their kitschy calendar sensibility. I was one of those guys who believed in straight photography, and what Ruscha was doing was simply straighter, photography degree zero, when photography became more and more transparent. It wasn’t about the photographer or virtuoso techniques. Ruscha was perfectly good technically. What is a good print after all?

When you were making your Prototypes, Greenberg was still king of the art influencers. Painters discussed “the mark” as a basic gestural component. Paintings were objects. Ed Ruscha fit into the Pop Art angle with his paintings and the Conceptual Art angle with the books. Greenberg certainly hated it. But an important element in art is how it’s made, and the way Ruscha’s makes painting is a lot more technically calculated than his photographs. He comes from old-school style of hand-drawn, hand-painted design. When he takes a photograph he doesn’t exactly seem to be looking for light—as many photographers do—he’s looking for content. His content was always incredible, but what he brought to the photograph was, for me anyway, something like John Lennon’s playing the piano, which he does perfectly well for his needs, but it’s not very good piano playing. I’m a fan of Ruscha, across the board, but I find that your photographs were and are always better because of what you bring to the material. Ruscha made books and good conceptual art, but not great photographs.

I like Ruscha’s photographs as photographs. I think they’re very good. The technique is fine. Robert Frank pictures are grainy and blurry and they look great. A meticulous Weston looks great, too. But what makes a good object depends on the intentions and what you represent.

The Bechers were in “The New Topographics” show. Were you already familiar with their work?

Yes, but only because I’d seen their show at the Ileana Sonnabend Gallery in New York.

Did you sense an artistic resemblance?

Yeah, but in a spectrum. In “The New Topographics” show, they occupied the most conceptual end while the most traditional photographer, who was also in the show, was my friend Henry Wessel. His vision — and the tradition he comes from derived from Friedlander and Winogrand. Stephen Shore was in the show, too, and the only artist to show color pictures. Nicholas Nixon made wonderful pictures, which he’d shot from tall buildings in Boston, New York, etc. Wonderful. He’d had another brilliant idea. He married a Waspy young woman with three sisters, and every year he took pictures of all four of the Brown sisters. Now they go back like 40 years, and we can watch their Waspy female aging process.

You start something like that but can never know how it will end up—marriage especially.

I’m not sure that was an obligation for him.

Were those pictures in the show?

No.

Stephen Shore was a neighborhood kid on Union Square and at 14 or so he was shooting in Warhol’s Factory.

All his shots are recorded in books. For “The New Topographics” he used a large view camera and made beautiful contact prints. The quality, tonal range, contrast, etc., of a contact print is the same in color as it is in black and white.

What were the critical reactions to “The New Topographics” show?

None to speak of. It was reviewed in Art in America—Eastman House paid the journalist to come, put him up, etc. That was it. Then nothing, though it traveled to the Otis Art Institute, because I knew the curator, and then it went to Princeton University, in New Jersey, in the summer, when no one is there. Then six months later people were talking about the backlash against the show.

Against it?

Well, I never saw a “fore-lash.” People said the photographs were cold, anti-humanistic—emperor’s new clothes. I liked it, and the show was redone again only a few years ago, which terrified me.

What happened in between?

By the mid-1980s people were talking about how influential the show had become. But when it was shown again I wondered what people would think, or even if it had been destroyed by its success. It doesn’t look the same now. And most people have been doing different—sometimes very different—work. Most of the photographers in that exhibition were always experimenting.

But it had an influence. Could that be because photography was also changing?

Yes, but it wasn’t a hotspot of controversy in 1975. I felt the show was ignored.

The New York art world was in transition from performance, minimalism and conceptual back to painting, expressionism.

I don’t think the product issue in art emerged until the 1980s, when Reagan’s counter-revolution and the deregulation of the stock market created a new class of rich people, who wanted art, as rich people always do. Minimalism and Conceptual art were already sorted out, very expensive, mostly unavailable, and, of course, very difficult for the newly rich collector, and, therefore, the last thing a master of the universe wants in his apartment. For most people, art means painting. Reagan era art buyers wanted apartment-sized paintings. They wanted narrative art, as do critics, because it gives them something to write about. Concrete art or abstract art is tougher. So the 1980s were, in retrospect, a pretty empty period. Your friend Richard Prince is one of the very few Americans who make art I’d be interested in seeing.

What do the Prototypes, Tract Houses, and the Industrial Parks have in common?

Things, homes, public places in general.

What came after them?

After the Industrial Parks, I did Maryland,which was a bicentennial work, 1976, organized by the Corcoran Gallery of Art. I drove east, got a sublet on Capitol Hill—a really weird neighborhood in the process of gentrifying. I went in the direction of the Maryland suburbs—during the coldest winter in recorded history. My then-wife came with me. She’d sit in the car and honk the horn for me to come back, so that I didn’t get frostbite.

What was different about the East Coast?

Everything wasn’t new, but what wasn’t new was generally dirty and broken.

Compared to Los Angeles?

Los Angeles had a little downtown from the Chandler era. But LA didn’t really exist. It had all these little cities growing up around it. It’s more like sprawling London. As John Gossage said, “On the East Coast is one endless slum from Washington, D.C. to Boston with a few silk-stocking districts packed into each one.”

What did you do after Maryland?

I came back west and photographed around Reno, Nevada, which was a kind of non-place, given to the Mafia, a state that was kind of a left over, different from but related to Vegas, without the Mafia. Later I photographed Park City,Utah, a similar place, given to Mormons. These were all places I didn’t care for, but highways ran through them.

Nevada, Park City, San Quentin, and Candlestick Point: what drove those subjects?

For Nevada, I had a Guggenheim Fellowship and was very curious about the state, because it was California’s grubby backyard, where things were thrown over the fence, where they kept mining, missile ranges, and the Mafia. When you drive east on I-80 from Tahoe to Reno you think it’s a godforsaken hole. When you enter Nevada, you know you’ve crossed a natural border. It’s exotic, and very much the West, where people are friendly and don’t ask questions, especially in northern Nevada. I was interested in that.

What about Park City?

I knew people in Salt Lake City, Utah, where I stayed. One of the tourist places, Park City, is located about 45 miles out of Salt Lake City. It was an old silver mining town, and one of the few places that didn’t have an overwhelmingly Mormon population. Miners were mostly Irish, and Catholic, not Mormon. What I saw was weirder than anything I’d ever seen. Years ago, when the Pan-Am building was going up in NYC, over Grand Central Station on Park Avenue South there was an illustration of the building standing on the moon, asking where could it look better. At Park City I thought of the moon. Tract houses were going up all over the place in a flat area, before you got to a canyon. They were all kinds of styles—Greco Roman, Log Cabin, American Colonial—and constructed by many developers, most of whom worked in multiple styles: they built a wooden structure, called a balloon frame, and tacked on a style with finish carpentry, the American way. They seemed badly built, like hellish madness. I was fascinated in the same way that I was making The Industrial Parks. I didn’t have to drive around looking for things to photograph. The landscape was changing constantly with new construction. The same area I’d visited two months earlier would be transformed. So I photographed there over a period of 14 months, coming and going from San Francisco.

And then San Quentin Point…

It was close to home, and I was in a difficult financial situation when I did that.

Were you teaching?

I was never known enough to get a teaching job. In fact I had to borrow a guy’s camera

What kind of camera?

Until then I used Leicas, but the film that I’d been using was no longer manufactured, so I had to use a more normal film, like a 64 ASA film, and I didn’t have a camera. So I borrowed one from R. Crumb’s lawyer.

I hope Crumb approved… The San Quentin Point images are also around this time, and similar.

They kind of came from the Bogart movie, Dark Passage, when he first escapes prison from San Quentin Prison, before he has a face change, which you don’t see until the end when his own face is revealed. I thought of that walking around the landscape. I was in dark mood myself, I’d just read Jonathan Shell’s book, The Fate of the Earth, and seeing the landscape as a dead man might see it. It had both wet and dry areas—not yet $1.5million homes.

Not unlike Candlestick Point…

That was the location of what would be the stadium parking lot. Its only value was as a parking lot. Anyway, I’d go out to those places, which were dangerous because the crack wars were going on, but then I realized that if they didn’t see the car, which I parked far away, I’d be safe. Candlestick Point was a huge weed lot. They wouldn’t even notice me. There was a powerful, politically active Black community, whose representative was Willie Brown—Downtown Willie Brown.

This was a period when you shifted from the Prototypes and the Tract Houses. How would you describe that change?

The space opened, and it was not a great time. It was between then and Candlestick Point that I culminated what I thought I wanted to do. There was more space in the shot, starting with Park City, and then by Candlestick Point, there’s nothing “in” those pictures. I’ve always felt that my series were codependent, but people always find a favorite.

Isn’t that just how it is?

Try that with Candlestick Point—they’re all pretty much equal, pretty much alike.

In Candlestick Point you have the Wizard of Oz moment where there’s suddenly color. What was that about?

From 1976, when Eggleston was first shown at MoMA, and a great furor was made over his work, we started to have the “new color”—the new American Color, the new British color, the new Western color. A market opened up for treacly looking calendar colors, like Joel Meyerowitz’s pictures. The color has been drained out. Most color was saturated. There was such an argument at the time, but it stopped being an argument by the end of the 1980s, so I used them both color and black and white.

Is that coincidental with black and white’s disappearance from the landscape?

I think normal pictures were black-and-white until about 1975, and then there was a lot of hullaballoo, and then after about ten years, the average picture was in color. Before that, magazine covers —even Life magazine pictures—and most so-called classy pictures were done in black-and-white. I wanted dusty colors, and had a certain amount of difficulty at the lab because the guy would always give me back art pictures. This was the first time someone else developed my pictures. I wasn’t willing to do color development. I had to find a nice, smart person, whom I could talk to and who would understand that I wanted an almost-black-and-white picture, but in color. Which was easy to do, but they wouldn’t believe that’s what I wanted. In the late 1980s you had a choice between two kinds of color: Type C, which prints from negatives and is subtle, very beautiful, but not very permanent; or Cibachrome, which prints from transparencies and is relatively permanent, like 75 years, and was high-gloss reflective. But everything looked unnatural.

Wasn’t Candlestick Point semi-matte?

Yeah. And Cibachrome worked fine as long as you weren’t photographing natural colors. A parking garage at night was perfect for Cibachrome. Shooting Yosemite Valley would end up being a fake-looking picture no matter what. It was a characteristic of the paper. All my night pictures were shot in Cibachrome. Anyway, they make a scan, and now they print with laser.

Nevertheless, Candlestick Point seems to mark a rupture or transition.

I was winding down from something. This was the piece in which I took everything I knew and used it and didn’t want to repeat it again, ever.

In a single piece made up of many photographs?

Yes.

Has it ever been sold in parts?

Not that I know of.

It’s like a strange scrub landscape.

I looked for that, because it isn’t a typical landscape.

Was it anything like Smithson’s looking for ravaged landscapes?

Maybe. I recently drove down the coast of Croatia. This was Ulysses’ landscape, and it’s remained largely the same. When I think about the landscape in Orange County, when and where I grew up, and looking at it today, they took paradise and created New Jersey in a generation. William Burroughs said that America was always evil, waiting there lurking even when the first settlers walked across the Bering Strait….

In the mid-1970s things started to shift culturally, inner-city gentrification grew, Americans were eating more and better European food and watching European movies, and starting to wear designer clothes.

We learned that Italian restaurants had things other than spaghetti with tomato sauce—and we discovered sushi.

You once mentioned to me that your retrospective traveling exhibition, “Rule Without Exception,” coincided with what you called a “paradigm shift.” Had you read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolution, where we get that term, and where he speaks of the artificiality of grand theories against the forces of reality? Was it any kind of influence?

Yes, I’d read it. He gave a term that explained what was going on in vanguard art as well as science, which claimed a belief in progress and a reductive logic, and how the investigations in art had become reduced to philosophical observations, which didn’t exactly resolve the business of art, selling paintings, and so on. It was an end game, where the only hope was to kick over he chess table. Artists were making minimalist and very specialist and elitist art that was inaccessible to most people.

Earlier you said you were perceived as an elitist artist?

Yes, because my art wasn’t figurative or narrative-based, and it didn’t speak to emotional issues, or certain political ones, because I was a White man from a middle-class background making art. Society wants to confine membership to important people, but artists have wanted to increase their public to come look at art. People don’t consider scientists as elitist, although the scientists who created NASA did so with information and skills people didn’t know about or understand, or even have to know, which seems elitist to me. So science got away from that criticism because science is taken more seriously.

Abstract Expressionist artists and Minimalist artist Carl Andre walked around wearing worker’s clothing; artists in the ’80s went from dressing like punks to wearing black. In the ’60s sculptors made art out of industrial materials, reducing materials to simple forms, which, to me, was a manifestation of the machine age—all Minimalist art was made by machine; Conceptual Art tended to resemble plans. In the ’80s art was modernist in spirit, design, and intention.

Art for a century— Impressionism, Cubism, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, Joseph Kosuth’s materialist representations, or even Lawrence Weiner’s word art—was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, which described a sculptural condition with industrial ramifications.

Your beautifully made images suggested something darker, also politically.

It was intended to be a subversive investigation of the phenomenal world.

So what was your paradigm shift?

With Candlestick Point I’d done everything I could working that way, with that subject. I was tired of working like a painter—tired of going into my studio, making prints, taking them to a gallery, and offering them for sale. The darkroom was work. I wanted to participate in a more potent way in people’s actual live, maybe by doing public projects. During this time, circa 1989, there was a centenary of Duchamp and baseball, and the 150th anniversary of photography. So a lot of places did their anniversary shows, but the photography shows tended to be somewhat empty. Photography had a history that most agreed upon, then after around 1956 it went in various directions. Add to that, Robert Franks’s, The Americans, which changed the emotional key of photography from European pathos to American irony. But for their centennial exhibition, the LA County Museum featured David Hockney. Others showed their best historical photographs. No one showed the history of photography as a contended area, because everyone pretty much agreed with it. I didn’t. The museums all did shows to validate that history. American art was also running out of steam, and newly rich stockbrokers wanted art for their apartment walls—small paintings, usually figurative, but not video, performance, photography, or sculpture.

How did you decide to change?

Spending more time in Europe where public projects existed. It was the end of the Reagan years, the first Bush years. America had changed for the worst. During the Age of Manet a chasm had opened up between the values of the bourgeoisie and the values of art. During the Reagan 1980s that breach was finally closed and artists became bourgeois. They made art for something other than it’s own sake. It was made for houses in the Hamptons.

Because their lofts got fancier and the galleries got richer—because of the art world?

I didn’t imagine it would be like that when I started out. I believed that art was oppositional, since Manet anyway.

Did you ever receive a stipend from a gallery?

No. I never asked for one. They weren’t gifts anyway, but debts against future sales.

Was Candlestick Pointlinked to this recognition? During this time photography changed in the galleries, which showed big ones like Jeff Wall’s painting-oriented photographs.

Jeff Wall made tableaux; the first years had many brilliant ones, but it couldn’t be forced..

Did you know Vija Celmins, and like her work?

Her work is amazing.

I interviewed her years ago. She had a small painting of a starry sky on the easel and I tried to get her to talk about her work in terms of geography and space and human thresholds. She wouldn’t have it. She saw her works as made by hand, the hand of a painter, and the paintings were about painting, and not about the thresholds of space or time or eternity.

Richter speaks the same way.

But they maintained their way of making art, while you wanted to move forward. How did you do that? And how did you live?

I never had a huge income, and there was never a lot of investment in what I was doing, so I wasn’t giving up so much. I suppose if I had a waiting list and a couple of kids in private school I might have thought differently. But I had nothing to lose, and I wanted to do something that interested me.

And so?

Whenever art museums were built in California they made site-specific works, usually with a photographer, who would interpret the site before construction. Joe Deal did a massive documentary site-survey for the Getty. I proposed something for the Newport Harbor Museum. I’m a native son and all that. But once I got there, I didn’t find anything to do. I didn’t want to photograph more land being churned up. I could do that easily enough, but that was all the more reason to not do it.

What did you do?

The first impression of a place one has left is that it’s smaller than you thought. It had also become expensive, but when I was a kid the only expensive property was on the water, and was mostly of interest if you had a boat. They were the luxury houses. Otherwise Midwestern Republicans had installed themselves on a not very beautiful part of the coast, but it had a natural harbor, which is why movie stars like John Wayne lived there. There wasn’t a Marina Del Rey, because of the coastline; there wasn’t a marina until you got to San Diego. One of FDRs works projects was to build a jetty maybe a mile long into the sea, which influenced the cross tides and made it more hospitable to small boats.

Then you somehow decided to do The Deaths in Newport project—a book about a local murder, with a Chanderlesque style of writing that really did evoke the era. Was that a personal matter?

That was a story that my father was fond of because it was fond of him—and a father I didn’t know so well, because he died when I was 12. I was fascinated by it. It engaged a preconscious, preverbal period in my life, when things went on around me. Once I decided to do it—and I wasn’t in a hurry—I researched all the newspaper archives, the Los Angeles Times at UCLA, The Herald Tribune, which was a Hearst tabloid—William Randolph Hearst was the Murdoch of his time. But his paper had closed the day before I had an appointment to visit their very extensive archives. It was one of the last murder stories before television. It wasn’t as big as the Black Dahlia, which was different, because there was no formally accused, where there was in this case, and the police did something they often do to find the guilty person: they convince themselves who did it, manufacture evidence, and perjure themselves basically to frame the guilty party. Quite a few innocent people are framed, but so are most guilty people. That’s how they get around tainted or wrong or inconclusive evidence.

Weren’t the parents who were killed the girl and her boyfriend rich?

Well, she’d have been rich had she been allowed to inherit the money. It was a very high profile case. The state’s attorney general cast his political fortune on it, believing it to be open and shut. But he lost. The defense made a fool of him, and he lost a case he shouldn’t have lost. He was not returned to office in the subsequent election, and he was the only Republican at the state level not to be re-elected.

It seems you want the work to be judged for what it is, as art, not as an extension of yourself. You’re presence is somehow at a remove. Did you ever see your art as being socially inclined?

Only in subversive ways—I never had much confidence in art that was scolding people. I don’t want to say that late Capitalism is wrong and that we shouldn’t do it. It’s more interesting to plant doubt in people’s minds?

What about a Larry Clark photograph, in black and white, of a pregnant teenager shooting up heroin: Is that moralizing, or simply presenting the dark limits of human life? You don’t want to know this girl, and yet it shows one of the terrible things we do to ourselves.

I don’t think about Larry Clark. But think about Manet’s Olympia. His model, Victorine Meurent, was a painter herself, and lesbian. She has the strongest look, returning the look of the voyeur, stronger than Mona Lisa, not beautiful, but not a femme fatale, a gamine … none of her works have survived, though there are notices of exhibitions. I was curious about her. Then I heard someone say that since she’s a citizen, and that there’s information somewhere in the French archives.

Art often gets one to think about the limits of acceptability or even morality, which, it seems to me, is one of the primary interests in life.

There’s more everything in America, more stuff. “I tremble for my country, for I know my God is a just God.” Jefferson. But after the Industrial Parks were shown and known about, though mostly ignored, they received one strong review from Alan Sekula: he thought they aestheticized something that shouldn’t be aestheticized. He cited Walter Benjamin’s remark about the Krupp factory, saying that if you saw it, you wouldn’t have the slightest idea what went on inside, which is certainly true about the Irvine industrial park, and their bays, or groups of bays, some of which were refinishing surfboards, some making instruments for the aerospace program. Walter Hopps’ remarked that you couldn’t tell if they were making panty hose or mega-death. But I thought more than that. One conclusion to draw from Benjamin concerns the inadequacy of the image and that we need a text to provide information about what’s happening. But the image wasn’t so inadequate, though maybe not for the Krupp factory. The Irvine buildings were intended to be camouflaged, to look the same. They all had a little sidewalk, a little front lawn, and some shrubbery. But no one walks the sidewalks and no one goes in the front door; they go in the back, where the deliveries are made. It’s a little beyond just confusion; they’re intended to be confusing and non-offensive, and to evade any curiosity about what goes on inside. They’re cheap to build and anything can go on inside.

That’s the modern industrial version of 19th century ateliers, which might make shoes or baguettes, or house a brothel. Assuming industrial parks or the assembly line, Taylorism, and the cookie-cutter houses are dangerous, systemic evil seems an exaggeration, including in Sekula’s negative critique…

He died recently, and was tendentious adversary—but one can always use a good adversary. He was always calling me to consciousness about the humanistic or Marxist side of life. He thought one should look at the workers. But Los Angeles was not really a working class community: it wasn’t a factory town. That aside, I started to think that photography always depicted factories. It’s even a byproduct of the industrial revolution—which stringed together many inventions. Photography was combined from optics and printing. It came into existence as a part of industrialization and repays its invention with decades of complimentary portraiture. If you look at modernist, Bauhaus, or the Bechers’ pictures, and most of what you see is industrial. You might hate it, but you’re not at sea about it. You can understand the pictures and also figure out what things were used for. You didn’t have to know about crop surpluses, but you knew what it was and the kind of world it represented. It was industrial. Everyone knew about specialization. It wasn’t for sympathy that Marx chose the industrial proletariat; they were exploited, but they were also the ground floor of the future. You could understand mechanics, the fittings and the parts, and how things might have worked, what they did. Of course that all changed after WWII when mechanical technology gave way to electronic technology and the black-box world, of which you don’t know what’s inside. Now they use the same mainframe computers to send out the mailings for La Redoute that they use for French nuclear targeting. What’s different is that it’s invisible. And we still don’t necessarily build different machines for every different function. That was the idea that began the “Sites of Technology”: they reveal very little, they’re a beautiful example of Platonic thinking, and in a sense, the more you see the less the know, but you feel satisfied that you’re knowing something, even if you miss the point of the function itself. You can’t deconstruct it like a machine. But this technology is also constructed with standard parts. They’d ask if I wanted to see the computer room, and I knew what I was going to see—a tiled floor raised about half a meter so they could run all the cords and wires underneath; if there was human work to be done, I’d see a counter space at midpoint, lit by strip lighting at between 50 and 100%, dimming to almost nothing at the floor. People who were softhearted would put up posters. I was only in one or two places where, when we left the computer room, someone turned off the lights, because they usually kept them on. They’re something more than a machine. There’s no friction. But it’s less ecologically sound than we are led to believe.

Visibility versus invisibility goes back to Buckminster Fuller’s theorem about technology evolving from tracks to trackless and from wires to wireless.

Bucky Fuller’s P.T. Barnum zeal: I think he was right about many things, and one of the best rabble-rousing public speakers I’d ever heard, though he was killed by the Cold War. Do you remember the DEW Line (Distance Early Warning Line)—the rockets and radars strung around Canada’s North Pole—our first signal that the Russian’s were coming? I remember because a friend sent me some photographs of a house that Antonioni and Monica Vita had commissioned on the Sardinian coast—a dome house, a series of intersecting white plaster domes, which reminded me of Fuller and surveillance architecture. They weren’t Fuller domes, but the architect’s. Because every Fulleresque dome I’d seen since the summer of love was ugly, clunky, and pieced-together with wood, while these were beautiful, more like the nave of a Byzantine church, painted white, and much closer in spirit to the space age. But I think the couple broke up before moving in

Are their connections between your work and filmmakers—or even feelings or sentiments related to films that got you to think differently?

Not American filmmakers. Hitchcock, because he was sinister, and English, and there was international cinema—Antonioni, Bergman, Fellini…

Which was mostly in black and white.

Yeah. There wasn’t much color. Antonioni’s Red Desert, Godard’s Le Mépris, which was magnificent. I saw movies at the local film club, when I was 14. Then when I had a driver’s license I’d go see the art galleries on La Cienaga Boulevard and international films. Growing up in Newport and Laguna Beach I knew about Hitchcock before there was cinema, when they were still simply movies. I’d seen the better Hitchcock movies. He was a master of suspense, a genre we loved, and was the guy who did it best, so he had quite a following, of people in general. In maybe 1960 I saw Fellini’s La Strada at the Laguna Beach Film Club, at a place where a dozen or so people who chipped in to rent films. Other films were playing in LA in repertory cinemas—Bergman, Truffaut, Godard, and Antonioni… It was called International Cinema. Hollywood had run out of gas, it couldn’t make Hollywood movies any more. International Cinema was establishing audience in 1959, ’50, ’61. If you wanted to see masterpieces of European contemporary art, you could only see its cinema. It was very hard to see European or even American contemporary art. I saw the first Warhol show at Irving Blum’s gallery. The LA County Museum didn’t open until 1965

What did you like about European cinema?

It offered images of a world completely different from the one I lived in. Europeans had a different emotional register and a different visual frame from American cinema—depending on the director. I don’t watch movies for the acting, I look at what the director does and wants to project. I really liked Eisenstein’s film, Alexander Neveksy.

In films, the camera pans, and when it stops on something, like the sled, Rosebud, in Welles’s Citizen Kane, the object becomes poignant, filled with potential meaning, if not specific meaning for the film. A single image in a movie becomes poetic because it stops and everyone is a prisoner of that moment; it becomes a symbolic image.

Single frames in films don’t really work, though, whereas single-frame photographs are made that way. In film, it needs the preceding and the following frames. And that was a lesson I learned.

Is that why you make series?

Yes.

So the way you make photographs is related to cinema.

I became more courageous and adept as I went a long, but by the time I got to Candlestick Point, there was no single image that was better than another. I wanted them all to be good enough and equal enough so that the piece itself, all the photographs together, would be one work.

You did that. Didn’t it make you happy?

Of course.

Is that when the rupture happened?

That was part of it. I realized, in a weird way, that I’d just succeeded in doing what I was capable of doing in that manner.

That’s an incredible recognition, and also an incredible decision, to move on, rather than to repeat.

Well, I wasn’t under the same pressure as, say, Frank Stella.

That’s one of the things that makes your work what it is. You had some sort of idea about what you wanted to do, and you made changes.

Not always correctly maybe.

California Minimalism—John McCracken, Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, as well as the Light artists like James Turrell and Douglas Wheeler—was very different from New York Minimalism.

The finish was different, and I think the idea behind it contained a sort of Zen or meditative sense, which was very different from New York Minimalism’s materialists like Judd, Andre, and Tony Smith. Larry Bell’s boxes are six sheets of glass, but they are optically so beautiful. When I first went to New York, it was so gritty; the whole town looked to me as if Richard Serra and Carl Andre made it. New York Minimalism is more industrial. LA Light and Space is completely different. There was a lot of amazing California art.

What about the Ferus Art Gallery, which had been paid for by Irving Blum, and Walter Hopps and Ed Kienholz ran it?

That was again too early for me.

Do you consider yourself a California artist, with the likes of them?

I’m too young to be in that group, but yeah. That was a great generation, and only five years older than me, but enough to make a difference. Think of Ruscha, who started working at 21, making work he’s still proud of, and is still making strong work. I’m sort of like a Jasper Johns type: I’m a lazy artist. I like to figure out problems.

New York art saw a change, in the works of Johns and Rauschenberg and Stella, who took art away from metaphysics and Platonic archetypes and into everyday recognitions. Artists, such as Vito Acconci, left the galleries to make public art, and did so out of a kind of fedupness with the gallery system. Conceptual artists looked at processes and concepts.

Conceptual Art delivered only half its promise—to dematerialize and decommodify art. They did dematerialize art, which is probably its most important gesture, but they did not decommodify art. The Capitalist system can consume anything. I was fed up with what I was doing, going off to shoot pictures for months, by myself; going into the darkroom to print for months, by myself. I was thought that kind of heroic art was finished. I was disgusted with the politics and economic policies of the United States; I was sick of how the art world was evolving in the 1980s; I was having or creating marital problems, and I wanted out: I wanted a different woman, I wanted a different house, I wanted a different town, a different country, and I wanted a different way of working, and probably some other things, too, like better food and wine.

So, was coming to Europe a conscious decision?

Yes. I had a grant to go to London for six or eight months, but it was so expensive I ended up staying only four months; I’d run out of money. I made some friends. I like British people, and how they think, but not the conditions in which they live—Five pounds for a crosstown tube ticket? People earning less and paying more. I think the spread was the better in Europe. I liked Paris—everybody does—but I fell in love with Berlin. Then I got into an argument with a guy there, the photographer Michael Schmidt, so I improved my German in order to better argue with him. I had studied German back in California. Then I was invited to give a workshop in Arles—I was taking every European invitation, in the 1980s—and there I met someone who lived in Paris. So I came here to Paris instead. But she was from Milan, so we also went there—and there I really fell in love, with Italy.

It’s too Catholic for me.

But it isn’t. The US has about 28% baptized Catholic, while Italy almost everyone is Catholic, but only about 25% of the population are actually practicing Catholics. But I lived there in two different circumstances, neither one of them requiring any engagement on my part with the government or a municipality. I first lived in my wife’s apartment. I didn’t have papers. I traveled a lot. In 1992, Italy started its first Office of Immigration. Nobody went there—though a lot of people were leaving Italy for economic reasons. I did public work. There was a project in the 1990s that echoed the DATAR of 1855, in France, which had catalogued the population and its development in France. In this one, there was a photographic proposal, which referred to photographers in the past like Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, and which mentioned my Tract Houses. So I was asked to participate. I toured Provance and found a place to work. And the body of work that came out of that was the Fos-sur-Mer.

What was that?

This was the first government-sponsored commercial industrial project, which happened where the Rhone meets the sea, Fos secteur 80. It was to be a state developed free-enterprise zone where if you put your French or EU factory here you didn’t have to pay taxes for a certain amount of time. I shot there.

Did living and working in Europe make it easier for you to get involved in public subjects, and public art?

Public art is a normal course for European artists, not for Americans, where it’s always been a disaster.

That happens. Vito Acconci generally makes proposals that are never realized.

You still have to deal with money people, public commissions, questions about your sex and race, but that’s more a factor in the US.

You said something earlier about the inadequacy of certain isolated images. There are a lot of photographers, such as Christopher Williams or Thomas Demand, where you need a description to understand the image.

I think American art viewers woke up to the idea that text and image were not an abomination. In an earlier time images were considered to be universal, everyone could read them in the same way: they contained knowable information, such as modernist photography.

Did photography and art also veer together toward the social and political, in which a context needed to be cited?

I thought form and content were all mixed together. Images didn’t always need texts, though some do. Sometimes images simply relate to each other, like in Ruscha’s 26 Gas Stations or my Candlestick Point pictures. When you see a group of images together, they create their own context, and, in a sense, their own text. That’s what interested me.

What about books, texts, catalogs?

The first book I did, The New Industrial Parks, had no text, just the titles of each piece, which was an implied text.

So, wasn’t it more like an artist’s book than a catalog?

That’s what I wanted. Artists books have only taken root in any kind of serious way after a couple of decades of Ed Ruscha’s books. Before him, artists books looked handmade, or like high school yearbooks with hand-tooled leather.

Since your retrospective, “Rule Without Exception,” you’ve made a number of public projects in Europe—including “The Power Trilogy,” which comes out of “Sites of Technology.” How did the technology pictures come about?

I was living in a Milan and I’d written what was for me a dream proposal to some people at Nord-pas-de-Calais, thinking up an idea that would interest them, while also trying to do something that would interest me. They were organizing bourses for people to do a project about life and the economy, which they thought would improve. It’s one of the worst-off areas in the country. They had about 25% unemployed, worse than during the American Depression. They were interested in documenting the effects of the trans-Manche tunnel between England and France. The attitudes on both sides of the channel were very different. The French were very hopeful, and thought it would bring prosperity, which it didn’t. You know, the way France works, the system of governance never changes; they simply change monarchs. The British, who were perhaps more sophisticated, thought only a select few would get rich, and are, in fact, the people who generally get rich. Also, the original tunnel would go to Paddington, instead of Waterloo, under London. I proposed to photograph the technological research areas of any industry or business that would be affected by the opening of the Channel tunnel in the next 30 years. They liked my project. They said that about once a month they’d refused a proposal from a conceptual photographer who wanted to walk the length of the tunnel and take a picture at every kilometer—sort of easy Conceptual Art. So I was pretty much given a blank check.

That’s generous.

But then, during this time, about a week after a dinner I’d had with a photographer I’d met in Japan, I got a letter from Kawasaki to come to Japan for one month and do a project with them. I said yes. Both proposals—in France and in Japan—kind of segued. The people at Kawaski were planning a photographic project for their 50th anniversary. They said I could photograph wherever I wanted at Kawasaki plants—they made motorcycles, televisions, and electronic products. They’d also got into a mess because they’d sold the Russians some kind of technology that permitted the Russians to hear and locate Western nuclear submarines. Kawasaki was questioned about it and needed to turn attention away from such humiliation. I stayed a month in Kawasaki City, which is between Tokyo and Yokohama, and has about 4.5 million inhabitants. It’s larger than all but three European cities. The Japanese feel comfortable buying things from mega-corporations that make many things successfully, like Mitsubishi, or Yamaha, which makes motorcycles and pianos. Kawasaki had also re-mastered D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance and held performances on the Imperial Palace grounds, which I saw. One of Kawasaki’s industries was involved in the Japanese Space Program. The Japanese have communication satellites in the geosynchronous orbit over Japan, for weather and communications, which are solar powered. So before I would do anything, I’d be invited a day in advance for a formal tea in the entertaining office of the director of a division, so that we would be known to each other. Then, and only then, when you’re known can you make requests. They spend a lot of time in formalities. Once a Japanese firm hires you, it’s a lifetime situation, and a lifetime commitment on both sides, so it’s very formal. They seem to see themselves as one tribe of people, which you’re in or out of. They regard Westerners the way colonizers looked at the people they rule. But they have a powerful code of politeness, so if you ask for something at a store or for directions, they’ll answer with complete respect. I guess it’s better to be racially discriminated against in Japan than to be relatively equal in other places. I spoke with an American who’d been there for 30 years, whose wife was Japanese. He ran Magnum and was a highly respected, but was simply a highly respected foreigner. The glass ceiling in a Japanese company is tight. The Japanese director of Sony US could never be a director in Japan after that—they’d been corrupted somehow. But I liked Japan, a lot, the people, and the cities, how they did things. Space is so precious that storefronts can be two meters wide, and tiny four-story buildings. I love their 7-11 Stores. It’s like the American idea but done so much better. One thing I liked was staying in a traditional Japanese room, but you could never get coffee with breakfast, so you could get a coffee in a machine. They have vending machines on the streets. In LA you can’t even find a payphone.

What did you do for Kawasaki?

One idea was to do a book about the company and technology, which I was one of three or four people to do. I was asked to select areas, and I chose AI (Artificial Intelligence) clean rooms, which are dust free. I had to wear a clean suit. I had some idea of what I was looking for.

What camera did you use?

A small Linhoff, 6 x 9cm, about the smallest view camera you can find. Long exposures, as usual—almost all my works are long exposures.

A lot of the pictures have yellow and blue machines. Any reason?

That’s the effect of uncorrected sodium lighting, which is what you get in clean rooms. It’s like Bruce Nauman’s Green Light Corridor: if you stand in there long enough it turns to white. Your eyes adjust, photographic film doesn’t. The photograph picks up the color of the light. Any light creates the color of objects.

Were you conscious of that?

Yeah, I knew it would do that. It was a part of the situation. I had to agree to Kawasaki’s rules. So, if I were looking at a monitor, there would be a piece of paper with the operator’s name and information on the machine on it—including the logo, Sony. They said they didn’t want to advertise their strategy—Sony had the best screens. I had to retouch that information out of the picture, which, back then, before Photoshop, was expensive and done by hand.

So did the direction for the “Sites of Technology.”

One of the things you learn when trying to reinvent yourself is that at the end of every day you’re still you. Speak with artists. Every young artist goes to every show they can, wherever they are. Older artists realize they’re stuck with their own sensibility and it becomes harder to steal ideas. I could never instrumentalize other people’s work for my own, so why even try?

What did you photograph in France?

The same. But one of the advantages of working in a monarchy is that the layers of government are interconnected. At a tiny cultural center in the middle of Paris I was given access to any company that was either owned by the state or that the state had shares in or that had amicable relationship with the state. I traveled around France with an assistant and a translator, and I got to see many places. France Telecom, which is like Bell Laboratories in the US, and operates with similar scientific rigor. One was in Bretagne on the Côte d’Amour, another overlooked Nice. They didn’t cheat themselves when it came to lifestyle. And one of the projects they were working on was a vocal payphone at which you could say the numbers instead of dialing or pushing buttons. I asked where they would put one, and how would they work with a foreign accent. So five of us tried, one succeeded, even among French speakers. One was across from the hotel where I stayed in Lannion, at the Côte d’Armour. There was a normal phone and the voice one, which was free. But no one used it because it never worked with a Breton accent.

What was their interest?

Voice identification. I asked him how they hoped to apply their studies, and they said they work on theory and on developing new technologies—they want to see what can be done. They do pure research, like at Bell Labs in the US.

That’s still part of “Sites of Technology,” which were in color, and probably needed to be.

Well, in the mid-1970s MoMA did an exhibition of Bill Eggleston’s work—their first color photography exhibition. And this started a landslide. Within a year, everyone was working in color.

Eggleston’s photography also look like the kind that someone else could do. It’s sort of like rock music, which doesn’t seem to require vast amounts of practice, though it really does. It seems easy, but it isn’t. Then everybody gets into the act and then new technology comes in to usurp the technique people once had. Eggleston’s very different from you. He pictures the world. One might imagine him, unlike you, being friends with rock and rollers like Keith Richards or Iggy Pop.

He’s played in movies; he’s rich; he collects guns. He’s sort of the William Burroughs of photography. Eggleston was a regional photographer, about the American South. I have no curiosity about that.

When you started “Sites of Technology” did your reading influencing you?