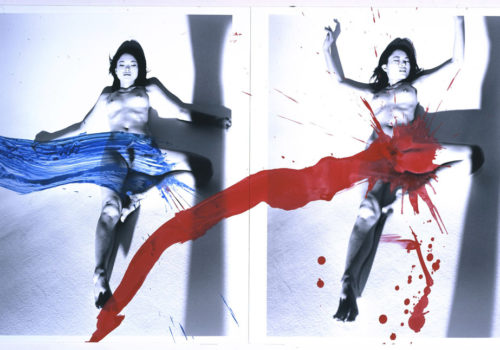

“To take a photo of people or things is an act which consists of framing reality, putting it in a box. […] Photography also binds people and puts them in a box. The photo begins in Kinbaku, in the act of tying up things and occasions.”

Madame Bovary in chains, or Araki’s martial art?

No, there is no way to deny the violence of the images. There is plenty to see for those interested in “Araki-pioneered” photography. We are seized by the powerful beauty of these images and also made uncomfortable. He explores an artistic territory which he didn’t entirely invent. Because in his series “Tokyo Lucky Hole” and the resulting book, Araki does not fabricate a reality, one of commercial sex or of hastily made pornography in a bar or hotel room. He sees it, he inventories it, he experiments with it to speak about the matter. From it, he draws an aesthetic. How can one not be hit by the force of the cover: a smooth nude image of a faceless young woman, fingering herself under a red dot?

I, a woman, a European, who for years has exclusively worked doing round-trips between cultures, am simply seized by the beauty of this image. Beauty is right about everything, especially moral judgement.

He cannot take with him centuries of art on all the continents, dismiss what we condemn as garbage, words or images. An image cannot kill, but it is good to remember that we sometimes kill (often, recently) for an image. The freedom to speak, to show, to create, to write, to shock, to change paths and to turn my look aside is there. I do not look if I do not want to come and see.

Many of these images carry, without a doubt, traces of domination of one individual over another. In this case, it’s a man over one or more women.

I can go even further in questioning the form that takes the bond to attempt unsealing the nature of the relationship between Araki and the Japanese judiciary tradition. Tradition is there. On the other hand, we will seek (in my opinion, in vain) the link of Araki with the images by Man Ray that were not meant to be published where leather encases the female body, within even more violent images.

But does the disturbing interpretation of Araki’s work also maintain this bitterly resented asymmetry of gender relationships? Because, in the end, it’s always the woman to whom we connect in Araki’s work. As a woman, do I not call for more equality among genders? Well, thanks should be given to Coco Chanel. She and Jean Cocteau, with the delicacy of gauze, she tied up the sumptuous body of Jean Marais for “Oedipus the King” (1937).

Bandage, bondage: the play on words is tempting. But then, we’re far from the art of a knot, an ancient practice of coercion that was based on an understanding of where to apply pressure on points of the body, a precisely encoded martial discipline (from the length of the ropes to their color, from the severity of the tightness to the proportion of the act’s gravity) which drew a series of drawn-in figures intended or not, at the very end, to the suspension of the guilty. The knot, humiliating, should remain invisible, the skillful combination should stay a secret. The punishment applied equally to men and women. The museum’s collections conserve a rare image of these shackles of ropes in a judiciary context.

Araki’s knots belong to Kinbaku, the erogenous constraining by ropes, whose first appearance seems to have been on the rise at the end of the Edo period. There finishes tradition, here starts manipulation, shaking certain prohibitions: the knots, banned as unsightly, make their appearance; the roping a symmetric contrary to the judicial practice of Hojojutsu.

Kinbaku was adopted in Europe, as a coded sexual practice, both in homosexual and heterosexual communities. It continued to evolve. That this practice of consented, reversible coercion, shocks my soul but not my eye may reflect the totality of its history: punishment in the dark folds of the bedroom. Araki made these, among other images, the subject of numerous books, and it makes me think of the last lines that Baudelaire wrote to his lawyer during the Flowers of Evil lawsuit: “What is this prudish morality, this puritan […] who cares about nothing but writing […] consoling books demonstrating that man is born good and that all men are happy […].”

(Extract from texte by Sophie Makariou)

EXHIBITION

Araki

From April 13th to September 5th, 2016

Curators : Jérôme Neutres & Jérôme Ghesquière

Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet

6, place d’Iéna

75116 Paris

France

http://www.guimet.fr

BOOK

Araki Nobuyoshi

Éditions Gallimard / Musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet

304 pages, 719 illustrations

39,90 euros

ISBN : 978-2-07-017955-8