Aerial photography has played a significant role as a source of valuable information ever since the First World War, when precise recordings of the zigzags of the trenches enabled strategic analysis and unprecedented accurate mapping. The evolution of photography picked up where Nadar—who took photos from a tethered hot-air balloon—had left off. It came to offer a fascinating new perspective, “the bird’s eye view”, which has fulfilled functional and decorative needs ever since. WWI was also a turning point for war itself, which is the real subject here. Changing in scope and countenance, war came to imply a multitude of nations, all of which would sacrifice of a generation of their youth. It led to the erection of countless memorials to the dead, statements in even the smallest villages of the savageness of war. Applied photography came to be used in a new way, resulting in topographic portraits void of human presence. Such photos were used to destroy human life, for they enabled military leaders to determine “with surgical precision” (a term favored by proponents of “clean” warfare) where strikes would be most effective. They could figure out which fields to inundate with bombs, which trenches to flood with poisonous gas, and onto which rises on the landscape to send young men to be torn to shreds. Photography, strategy, tactics.

Nowadays, WWI photography appears to be a blend of historical record and graphic illustration. I wonder what we can actually see in a photograph.

A mere century after the calamitous Battle of Verdun, Darfur, in western Sudan, has become tragically famous for the Janjaweed militiamen, the “devil’s horsemen” who wiped out 400,000 human beings—men, women, and children—while the officially sympathetic international community averted its eyes and ears. And in between these two bloodbaths, the Second World War coined the “scientific” approach to war and human destruction, not to mention the terms genocide and the final solution. By this time, the status and function of photography had already changed. The so-called golden age of reporting was fading fast, as doubt spread about the reliability of the testimony and images relayed massively in the press. People knew that WWI photographs had been crafted to serve propaganda, not knowledge.

This raised the question of whether photography is even capable of providing knowledge or information, and if so, what type? And on what basis? Once raised, such questions become impossible to shake. Doubts about the function of photographic images have only increased with the decline of the press, a medium that chose to ignore that it was being replaced by television, a far more efficient means to relate what is happening in the field. In any case, photographers, journalists, and even cameramen always arrive on the scene after the rapes and burnings have taken place. Sometimes there are dead bodies to greet them and provide certain photographers with subject matter, but dead bodies look much the same from war to war, continent to continent, and disaster to disaster. They are meaningless funeral litanies, tangles of syllables at odds with the apparent “realism” of the photographic image. Hell always has been paved with good intentions, and photo-journalism is no different. The myth of capturing extraordinary moments during the Vietnam War may well have faded, yet photo journalists have vainly attempted to hang on to this illusion. Is this naivety, shrewdness, sincerity, or a fundamental instinct for survival? Or have photo-journalists simply lacked the humility to go and see Goya’s “The Disasters of War”? In any case, they have unfortunately missed the opportunity to produce literal, illusion-free documentary pictures or to simply accept their inevitable subjectivity. It is a pity.

The world has changed and so has photography. Its inherent nature and use have become decidedly complex as the 20th century Era of Photography has given way to the current Age of the Image. Analog photos used to constitute a visual form of memory. Photographic legitimacy was rooted in a capacity to keep the world at bay, and photography responded to our urge to dominate reality by providing complete sets of pictures to replace it. Claiming to “faithfully” reproduce and record reality, photography essentially rendered it unreal. Reality became virtually inaccessible, for our most basic way of experiencing the world—through physical contact—was increasingly filtered through veils of interpretation.

We are now living in the Age of the Image, and filters are structural rather than external. Most images have become virtual, much like financial and stock markets, yet they still drive perception. Meanwhile, the sheer mass of pictures produced and circulated has made it nearly impossible to make sense of what we see. Countless, continually changing images simultaneously enrich and destroy. They are impossible to decipher, and we are reverting to a state of image-illiteracy, just as Walter Benjamin predicted.

The universe is now ruled by Photoshop et. al., and virtual and instrumentalized imagery is unremarkably ordinary. Surveillance cameras (sound recording systems were only the tip of the iceberg) are providing artificial answers to irrational desires for protection that only increase very real threats of terrorism. Big brother is not only following you into your tomb but is also perched on an orbiting satellite, watching everyone everywhere. You may call it knowledge, but it is still a delirious power trip. Reread Michel Foucault.

Indeed, satellites record, transmit, save, and accumulate coded image data and numeric sequences. The data is revised and re-colored as per NASA protocol to generate attractive pictures to present to the world. These images are as far removed from “truth” as the analog photos on which we once based now-shattered beliefs. We look at arrangements of shapes and colors as if they are illustrations, but only the research scientists who made them are capable of interpreting their meaning. Interpreting, not believing. Do we know what the images we see truly signify? As always, we need to know the context and function of an image to determine its purpose and eventual meaning.

What am I looking at? And when I look, what is genuinely comprehensible? I see shapes and know only what I am able to deduce by drawing from within myself and re-interpreting shapes I recognize. Photographs do not provide information. So we project knowledge gathered or gleaned elsewhere—sometimes from other photos—onto and into them. If we have learned how to analyze contextual factors, we focus on the circumstances in which photographic images are being presented to figure out what the intentions of those who are showing them might be.

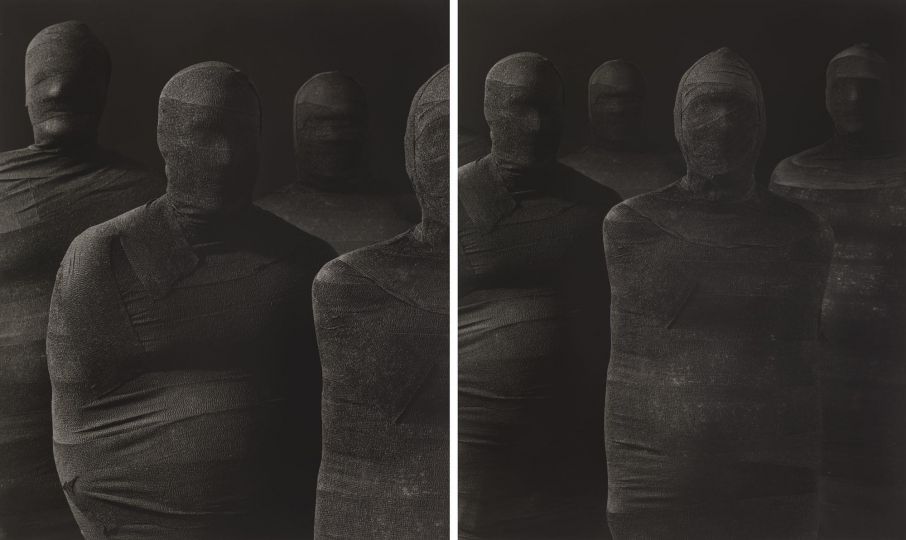

Camera-equipped satellites tirelessly circle the globe and record picture after picture of the surface of our planet—and other planets—in an obsessive endeavor to capture each and every detail. Hence the images of the remains of Darfur villages burned to the ground between 2003 and 2006. Satellite cameras were not intentionally looking for these images; they exist simply because the cameras “see” everything. The resulting color or colored pictures sometimes are, and sometimes are not, realistic. In one of them, houses are burning. A thick blanket of black smoke hangs above a massive wall of flames. Other pictures show barren, desert-like expanses. Beige-toned wastelands occasionally dotted with black or red specks. Still others, while open to interpretations, seem to suggest the presence of trees. Analysts have left red marks indicating where homes once stood. The only things clear to me are the abstract displays of color. You can see without knowing what you are looking at.

What purpose might these images serve? As far as Jacques Pugin is concerned, they can serve to raise, or at least shape, questions. Questions like those mentioned above. Jacques has removed the color from the images and returned to graphic black and white, distancing us from figurative representation and pulling us back to the early days of photography. To get even closer to these roots, Jacques has inverted the black and white to make pictures reminiscent of negatives, once the fundamental basis for photographs. In the beginning, photography was a process of capturing imprints, a transcription of what happens when light meets and then flattens the solid stuff of reality. Photography used to re-present tangible reality.

What I see is shapes. Lines that could have been made by an etching needle on a black metal plate, a criss-crossing pattern that reveals the inner whiteness of the metal. Goya used to cut into steel plates. To make pictures of the disasters of war to be printed on white paper in black ink.

Jacques Pugin has taken shapes and images defined by others and produced by machines, and he has made them his own. What a modern course of action. He has interpreted the pictures, and now they ask his questions. Calmly and quietly, they ask: in today’s world, how can we show what war really looks like?

BOOK

Les cavaliers du diable

Jacques Pugin

30 x 30 cm

64 pages

300 copies

http://editions-jacquespugin.com

http://jacquespugin.ch/livrescatalogues.html

http://jacquespugin.ch/les-cavaliers-du-diable.html

EXHIBITION

Les cavaliers du diable et Sacred Site

Jacques Pugin

Until March 14th, 2015

Galerie Esther Woerdehoff

36 rue Falguière

75015 Paris

France

http://jacquespugin.ch

http://www.ewgalerie.com