David Yarrow, 49, was born in Scotland and is currently based in London. He was named Young Scottish Photographer of the Year at the age of 20 and in the same year covered the World Cup in Mexico for The Times. His photo of Maradona holding the trophy aloft was internationally syndicated and remains an iconic image of that tournament.

David has since turned his lens on the natural world. He is the author of two fine-art photography books: Nowhere (2007), and Encounter (2013). Many of the monochrome shots that feature in Encounter were captured in East Africa. He is closed to Tusk, the leading African conservation charity, for which he is the affiliated photographer. Tusk, whose Royal Patron is HRH the Duke of Cambridge, receives 10% of sales of David’s prints and books to support its 53 projects in 18 African countries.

Ride the Ghost Train

For reasons I struggle to articulate, I have always been drawn to ghost towns. But having fulfilled this desire, I have been disappointed in the reality because invariably the lure of tourism has necessitated some immediately obvious modernity in the architecture. There are, however, a few villages from the gold rush in America that remain as they were left and after exhaustive field work, I found the best final frontier ghost settlement imaginable. I cannot reveal the destination for obvious reasons, but I persuaded the local government to open up the fenced off historic site for me.

It was a treasure trove of artefacts from 100 years ago – and best of all, there was a railway station and an abandoned carriage. Inside the carriage there was a dreamlike canvas on which to tell a story – snow on the rotten seats, broken windows and a central corridor strewn with the remnants of decades of decay.

On my first reconnaissance to the site, I saw the possibility of telling a story, but in a dreamy creative moment I thought I might need a wolf and some brave girls. It took some time to get all the logistics in place and I then needed the support of some talented and adventurous locals. We needed to shoot early for the light to be right and for the temperature to drop well below freezing – the wolf’s breath makes such a difference to the story within the picture and would not have been possible after the light and with a rise in temperature.

I am proud of this shot largely as it is difficult to know how it could be bettered. It is a reward for homework and logistical precision, but it is also testament to the animal handling skills of two people that were in the carriage that the lens could not see. This image will never, ever, be recreated.

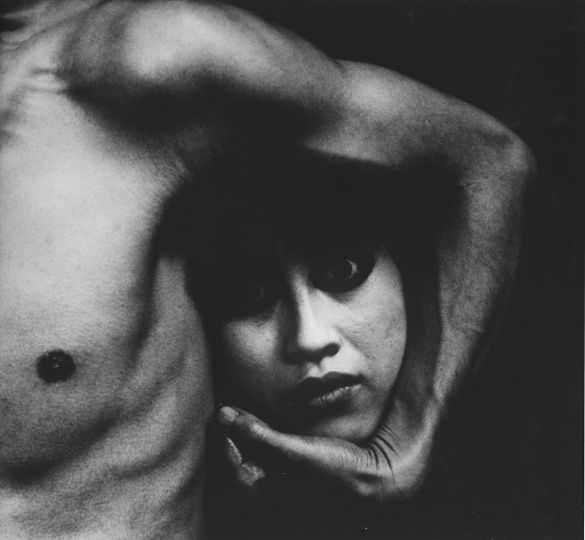

Mankind

Over the last few years I have taken some pictures of wildlife that grab the eye because of their composition, aesthetics and content. I have tried to explore new angles and new methodology to garner fresh content in a content-spoilt world. There have been many proud moments.

But I have never sought to be pigeonholed as a wildlife photographer – after all, I started my career at the World Cup Finals in Mexico in 1986. Maradona was and is an extraordinary man, and we can perhaps empathise with his ups and downs because we are human too.

Human documentation can have an uncomfortable proximity, simply because we understand more about the subject than we could ever do with animal wildlife. I have long wanted to travel to the cradle of mankind and immerse myself in a daily life that – whilst alien to us – is still human life.

In my view, the rawest place left on earth is South Sudan, which is still recovering from a shocking civil war. My friend Levison Wood – an ex-Para and veteran of Afghanistan – has just walked the length of the Nile, a feat documented in a widely acclaimed series on Channel 4. Knowing my desire to push boundaries, he encouraged me also to go the extra mile and travel north to the deeply tribal South Sudan.

The logistics and regulatory red tape involved in traveling 200 miles north of Juba (the capital) on water ravaged roads, to photograph a previously unfilmed Dinka cattle camp were formidable, but equally I knew that these hurdles precluded most sane people from entertaining the idea, and that I therefore had a chance of capturing something special and fresh.

I had a preconception of the image that I wanted to return home with – something that conveyed the raw enormity of a Dinka cattle camp in an elemental and biblical setting. Something timeless and vast. Like a Rembrandt, I wanted people to be able to look at the picture for hours and find new stories each time. I was indeed the first photographer to visit this 25,000 strong cattle camp, which was close to the heart of the civil war last year, and I felt a responsibility to get it right.

The Dinka was fascinated by my skin and my hair – indeed many of the children had never seen a white man. They did not care about my cameras – cows are their passion and on Lev’s advice, I brought A4 pictures of Highland Cows from Scotland as well as local cow medicine. I won the crowd, as they were transfixed by the Highland Cow images and equally grateful for the medicine. You reap what you sow with tribes.

On that glorious evening – 28th December 2014 – I did a good job, and the two days on a shocking road, followed by hours of walking in 42-degree heat and then wading through four feet of water known to house the odd Nile crocodile, were worth it. No other filmmaker has managed to get to this location. After an unnerving chest-deep re-crossing of the river at dusk, the rest of the long journey home seemed to go quickly. I knew what I had on my memory card, and I was elated and excited. I could not wait to show people. Two days later the Daily Telegraph – without precedent – gave it two pages.

In retrospect, I did one clever thing – I brought a ladder, because I wanted to silhouette any key detail against the smoke, which the Dinka create to fend off mosquitos, rather than against the setting sun. After all, we have all seen a setting sun and the clichés it can offer, whilst most have never seen this degree of controlled smoke. The smoke gives a sense of place and an ethereal countenance. Mankind is heavenly on one glance and Dante’s Hell on the other.

It was a long way to take a ladder – perhaps further than anyone has ever taken a ladder in Sudan. The Dinka looked at it as if it were a freak of engineering. What a good decision that ladder turned out to be. I will never reveal this exact destination to anyone, why would I?

One Foot on the Ground

I knew that this image had energy and an abundance of content, but I only fully understood its power to engage from its social media popularity. There are many parts to the image that contribute to its strength – such as the dust that the lion has kicked up or the late afternoon light on the water reeds. But most of all, it is the lion in full flight that is magnificent. Yes, I am proud that the image is technically perfect when I am quite obviously in harm’s way, but the image is made by him, not me. What a gorgeous animal – surely in grace, power and beauty it transcends all other species. We should be most careful not to lose them from our planet. And that late afternoon, he had just the one foot on the ground.

No Nearer

The hippopotamus is an extremely difficult animal to photograph in a way that is either different from the generic ‘mouth open’ offerings, or in a way that truly portrays an adult’s bulk and menace. They are dangerous animals and it is foolhardy to get too close. This is as close as I ever want to come to a protective adult – particularly when I am in the water. Hippos kill 3,000 people a year in Africa. There is a haunting intensity to this image – and it has an almost hypnotic pull that draws our eyes back time and time again to the adult’s eyes. Her eyes convey many emotions – protection, anger and alertness, whilst I am sure my eyes at the time just conveyed fear. She probably weighed the same as twenty adult men combined. The baby hippo also offers great context to the enormity of an adult’s face. The early morning light and the adult’s wet face combine to offer detail on a facial bone structure that is bordering on prehistoric and quite without equal. I am so proud of this picture, which was taken just twenty minutes before I had to leave the Zambezi to find my way home. The previous few days had yielded nothing.

Family

This is a special picture taken in a special place. Amboseli is the best canvas in the world on which to photograph elephants. In late October the lake is dry and huge herds make the daily trip across the scorched earth in search of water. This group contained elephants of every age and they composed themselves with great consideration for my lens. The protective instincts of the adult on the right of the image draw the eye in to the centre of the photograph. When I took the picture, there was no other vehicle within at least five miles – that is the joy of Amboseli.

The Prize

This was a memorable morning and the culmination of a great deal of observation and homework. I had worked with the same lion pridein Amboseli for four mornings, but the hurried placing of remotes at sunrise is a low-percentage and dangerous pursuit near lions. After some unsuccessful mornings, we covered the camera casing in Old Spice stick aftershave, as my guide knew that lions were attracted by that smell (the local Masai and indeed colonialists have worn it for years). It worked, and the lioness came straight towards the camera against a clean backdrop. The image is best printed at this 48″ size, simply because I used a wideangle lens and the resultant file crop is not immaterial. Amboseli is not a studio – indeed, a second after this image was captured, the lioness took the camera casing in her mouth and walked 700 yards into the bush. I was emotionally exhausted and it was only just after 7am.

Big

This was a pivotal split second in my photographic journey. Elephants are big animals and their enormity tends to be poorly conveyed by a camera lazily occupying a four-wheel drive – but equally to lie on the ground so as to capture a more menacing ground up angle is highly irresponsible to the point of being potentially fatal. The solution is afforded by remotes, but these have to be placed in the ground and personally checked with the lead elephant still 120 yards away. So much can go wrong – the elephants could change their path; dirt could blow into the lens or – as on this occasion – the positioning can be too good, and £7000 of gear could be trampled on. I thought that the camera would be lost and with it this image as the lead bull came within one final step of the remote. My savvy guide told me to keep on firing the motor drive – just with added intensity – and as he suspected, the bull was sufficiently conscious of unfamiliar noise in the dirt to stop and sidestep the camera. It all happened within ten heart-pounding seconds and when the full herd passed by, I rushed expectantly to gather the camera. As soon as I saw this frame, I knew I had a gem of an image. The 35 mm wide-angle lens was able to capture the whole elephant from foot to eye in sharp focus and the composition around it was extremely fortunate. I have tried dozens of times since then to take another remote control image, but nothing in content, light or composition touches this lucky photograph – which is now with us forever.

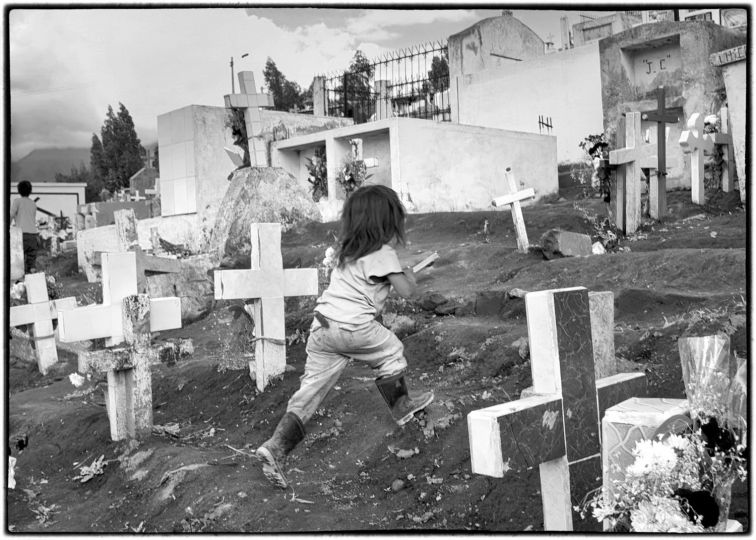

Easter Sunday

This picture is not the product of camera technique; it is the result of solid logistics and the investment of time and emotion. These Suri villagers near the Sudanese border are not accustomed to westerners and I had to gain their trust and commitment to help. The key to securing this degree of cooperation was to win the support of the tribal chief and this in turn required meeting him when he was sober and approachable. To work safely and effectively in Kibbish is a project that ends with a picture like this, but begins many weeks before. To me this image conveys dignity, pride and grace. It was the most extraordinary Sunday of my life and it was actually Easter Sunday.

Girls on Film

To tell stories is liberating because we do all become too immersed in the repetitious reality of daily life. It is good to dream and to conjure up imagery that is the stuff of fantasy. This is never far from my mind in Africa because we all grew up being told African wildlife stories. But to me, this photograph is as much about light, line and curves as it is about the story. There is a great deal going on within this picture. No one has ever before stood on this remote sand dune with this surreal image in front of them and that is good enough for me. The story unfolding belongs to the imagination of the buyer, not the artist.

The Jungle Book Stories

There are only about 1700 Royal Bengal Tigers left in India – a frightening decline from the estimated 100,000 during the Raj. Therefore, to find a father and son bathing in the same pool in the jungle was statistically unlikely. Photographers cannot direct wild tigers and thus the positioning of the animals relative to the surroundings or each other is matter of luck. Overtime, luck will average out, but the placement of the adult tiger’s left ear covering his son’s right eye enhances a picture which evokes jungle book stories. I like the lone eye to the right – even though it’s outside my focal plane, it ironically grabs our focused eyes.

Grumpy Monkey

The Snow Monkeys three hours west of Tokyo are accessible even in winter and it is difficult to capture fresh detail. This picture, on a bleak and cold winter’s day, probably works because everything about it is miserable to the point of being comical. The misty and dank weather matches the Snow Monkey’s mood. I had no light to play with and this is technically reflected in the lack of depth of focus. I am flattered that so many people adore this picture – maybe it says a little bit about us?

Jaws

When my curtain is drawn, this will still probably be my most widely published reportage photograph. It came after twenty eight unsuccessful hours lying face down on a boat deck in False Bay near Cape Town. Sharks only tend to predate on seals in the early morning and there is no reason why this should happen anywhere near a boat. The odds are low and patience is a most necessary prerequisite for this type of pursuit. This shot was captured on my ninth winter morning at sea and its clarity is great testimony to the capability of professional Nikon camera bodies and lenses. In darker hours after an unsuccessful shoot, I sometimes have to remind myself that this is my image and always will be.