Regardless of what one thinks of François Hébel—and the opinions can be extreme—one thing is undeniable: during his thirteen-year tenure as the director of the Rencontres d’Arles, he increased its attendance tenfold, turning a small event into one of the world’s most important. De facto it is a significant contribution to the recent history of photography and its development that this charismatic man of communication conducted.

A little more than a year since the announcement of his decision to leave the festival, Hébel agreed to speak to us. We discussed his “reign” in Arles, his desire to break with its conservatism by turning towards new forms of photography. He shows no signs of bitterness, nostalgia or regret, speaking of his future projects and of a world in which, “everyone has a camera in their pockets and became photographer.” His vision of the medium defies his supposed attachment to tradition. He was driven by the desire to bring something else to the city of Arles over the years. His dreams were more social than cultural.

We met in a bistro of the Marais district of Paris. He seemed composed and defensive, a position he had to maintain over the years. Him who qualify as a saint patron to photographers, he had to bear the diatribes of some, depending on their obediences and the court rumors. And that’s to be expected of someone occupying such a coveted position. The festival, says Hébel, “was more pleasure than work. What an incredible opportunity! It wasn’t easy, of course, but it brought me so much pleasure […] It was so exciting to have lived through these years of exchanges, to make connections with the general public, while promoting artists, photography and its specialists.

The latter were less common than they are today. “There were at most 200 people who knew what they were talking about and perhaps five serious collectors,” he says. “What I tried to do in the past 12 or 13 years was to bring these specialists into dialogue. For me, there aren’t different kinds of photography—there’s just photography, indivisible, which ranges from the most amateur work to the most high-concept. I’m certain of it. Quite simply, we need to find modes of presentation that can accommodate this variety of means of expression. Photojournalism, for example, which is more narrative, works best when it’s projected. Hence the idea of sets and ‘spectacle.’’”

Spectacle, yes, “but that doesn’t mean [he] likes drama,” says Hébel, in response to attacks that have been leveled against him. “As long as I could deal with it myself, I had no reason to make the internal problems of the festival public.” Hébel, was raised in a community spirit in the north of Paris at the end of the 50’s among actors and journalists who, “dreamed more of society than of culture.” He was far away for photography when he did his first internship at the FNAC, then became an assistant editor at Contact with Gil Mijangos before becoming its editor-in-chief. Back when the photobook market was still in its infancy, with Claude Nori of the publishing house ContreJour, Hébel developed a kind of “poor man’s portfolio” which consisted in putting ten photographs in a box with four pages written by a journalist to explain the photographer’s process.

Meanwhile, Hébel worked with Mois de la Photo, organizing exhibitions and events. Introduced to Lucien Clergue by Jean-Luc Monterosso, he took over the directorship of the Rencontres d’Arles for the first time in 1985 for two years before returning in 2001. From 1987 to 1997, he served as the director of Magnum, the famous photo agency which some would later accuse Hébel of giving too much exposure at the festival. “That’s not true,” he says. “It never prevented me from working with other people. Yes, I invited Martin Parr and Raymond Depardon to put together a program, but the former included not a single Magnum photographer and the latter very few. I also gave the opportunity to Nan Goldin and Christian Lacroix, who had no affiliation with Magnum. You know, people talk so much, but when you take the conversation a little further, you realize that it’s been years since they’ve seen certain things at the festival, like the evening projections at the Théâtre Antique, for example. In almost 13 years, you can imagine how things change!”

Because photography is changing, as is the way people perceive it. “For me, that’s photography, that gigantic territory that ranges from the purely creative to the vernacular,” he says. Regarding the vernacular, he discusses two projects in particular: “I did an experiment where I asked all the mayors in France to send me photographs of memorial statues in their cities. It served not only as a way to gather photographs of national monuments, but to see what a country is capable of in terms of the quality of its photography, from professionals to amateurs. The result was perfectly respectable.” The other project concerned the Parisian suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois. A year after the 2005 riots, Hébel was asked to put together an exhibition featuring the work of 14 professional photographers. He refused but invited local associations to explore their own archives. “Everything was there in the file cabinets of the town halls. It was incredible! I made 18 books out of it.”

He maintains an interest in the potential of amateur photography, as with Foto Industria, a biennial in Bologna devoted to industrial photography. At the request of arts patron Isabelle Seragnoli, Hébel is organizing fifteen exhibition revisiting the work of commissions from the greatest photographers to anonymous ones. It serves as, “a way to look at the world of employment and companies, and to think about one of the most common genres of photography.” The next edition will be held in October. Until then, an exhibition devoted to Harry Gruyaert, which Hébel curated, is now on display at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, and a tribute to Lucien Clergue will go up at the Grand Palais in the fall.

When asked if he feels as though he “came full circle” with Arles, Hébel says no. “I had ideas for the next ten years. We had to stop throwing money out the windows and start making long-term investments […] But when you lose half of your working resources and the whole public sector turns against you, what can you do?” But he’s not nostalgic. “If there’s one thing I never feel, it’s nostalgia. I’m more interested in the next project, the next photographer I haven’t met.” He wants to expand the horizons of the medium. “And I tried to do that every year with a dozen curators […] And I knew every photograph in the exhibition. That, to my mind, is the role of the artistic director.”

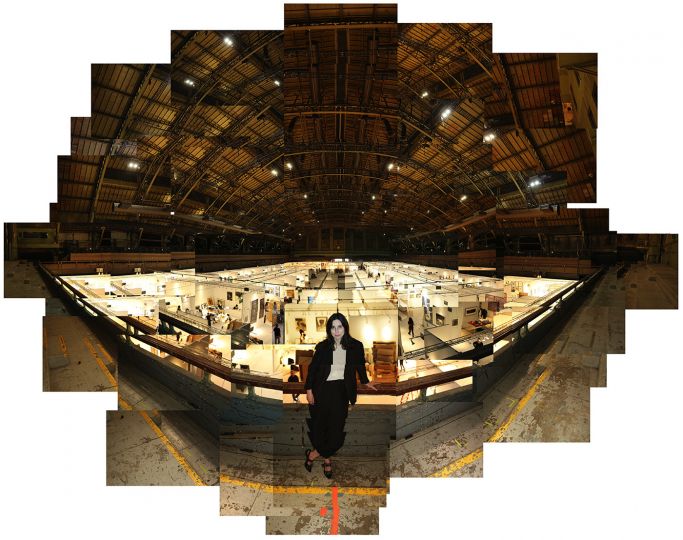

Hébel looks back at what he created at Arles over the years. For example, the 10,000 visitors given free access to the festival. “My project wasn’t only to promote a kind of photography that would never have been given the time of day in Parisian museums that only care about the dead. It was also a more far-reaching project, a political and societal project that would make people want to come back every year.”

An inveterate lover of Arles, Hébel defends the city with passion. While he remembers the many battles he fought there, he has also never forgotten, “its capacity to give you time to think to see, and exchange differently.”