Absurdities can say a great deal. An oversized tie invading London and taking control of the street could seem crazy; however, it is extremely real. What is today’s London if not a center of global finance, a megalopolis at the hands of white-collar workers? More than thirty-five years after Margaret Thatcher’s nomination for Prime Minister, England has forgotten that it was a big industrial country. Laborers were overwhelmed by the 1980s. Other Western countries, the United States and France in mind, had also experienced the shift from a secondary, manufacturing based-economy to a tertiary, service-based economy, often with as much violence. But how to photograph these new elites who wear formal suits as class uniforms and who are surrounded by an environment of offices and white walls? When arriving in London in 1972, Brian Griffin received an assignment from the English magazine Management Today to photograph the working world. For Griffin, failure was hiding everywhere. Even though the artistic director ( formerly of Camera, a trilingual photo-magazine) often compared him to Robert Frank, nothing satisfied Brian Griffin. People posed motionless before the camera.

It took him two years to take what he considered to be his first good photograph, London Bridge. The photograph is taken from the back seat of a taxi. In London, a horde of passers-by in line with their backs to the camera are contained between two guard-rails of a bridge. In this image, there are a few of Brian Griffin’s fixations: the uniformity of the bureaucratic society, the violence and absurdity of the world, and the punishment of man. These concerns were the result of personal experience. Brian Griffin was working for a daily paper that was miles away from the glamorous and subversive images of 1970s photographers. Receiving assignments from Management Today to photograph employees and bosses, he noticed that he was sharing a number of their habits: waking up at 5:30 in the morning, coming home around 8:30 at night, and, in between, spending days dedicated to work. In the 1980s, he wrote, “I probably live the lifestyle of a management executive, so I’m sort of one of them photographing them.” This common destiny worried Brian Griffin, turning to photography to avoid what would have otherwise been his fate growing up in a working-class family in the Black Country, an industrial region in the center of England. Certainly, he no longer worked in a factory, but was the life of an executive any happier?

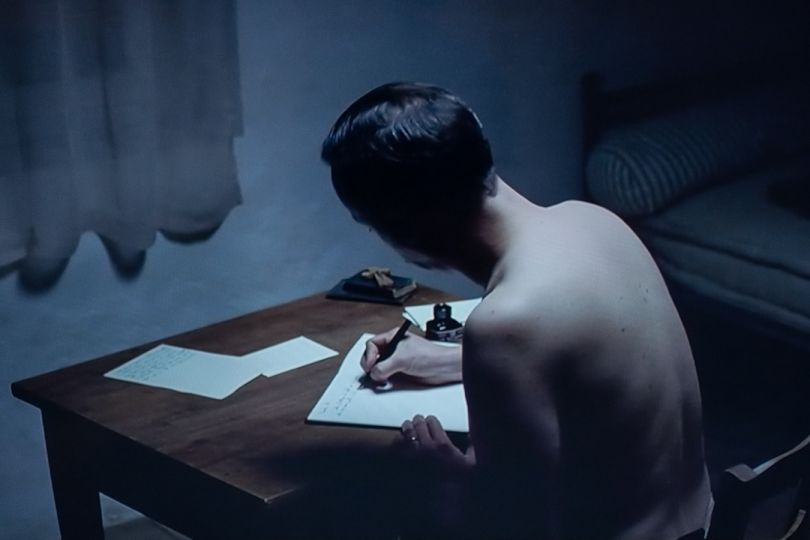

Brian Griffin continued to address this cross that men bear in Copyright 1978, first self-published photography book in England. The most iconic Stations of the Cross and Christlike torment are there. In Ballroom, an image made during his apprenticeship at the Manchester School of Photography, a man with his back to the camera wipes his forehead with a cloth, following the example of Veronica in the Sixth Station of the Cross. A trip of his to Moscow in 1974 is also used. Curious onlookers gather around what could appear to be Mount Calvary, and a man stands alone on a memorial reminiscent of the crucifixion. In 1975-1976, Martin, a friend of the photographer, was photographed in the intimate and aesthetic decor of Brian’s apartment. He mimed the descent of the cross onto the photographer’s bed, then the ascension in a photograph which Brian used as the cover. Two bottles of wine set on the formica kitchen table echo the blood of Christ. However, Brian Griffin does not mimic the death of Christ. He shows how much the Passion is unexpectedly found in daily life, deprived of its contemporaries. The sets are simplified to the extreme. The characters naturally dressed in dark suits. This could be anyone, anywhere in the West at the time. Brian Griffin grimly noted that his agony was shared and lived by others .

This darker side of his work is found in a project for a group exhibition at the Photographer’s Gallery in 1983. The photographer chose to respond to the given subject, London at night, by dealing with a nuclear attack on the city. While the Christian iconography is less obvious, the photographer continues to evoke the transcendence and presence of the invisible in the tangible world. To do this, he uses an inherent photography trick already present in his work from the 1970s: the halo of light. This brings to mind the halos of saints like those from solarization, a technique held dear amongst surrealists. Because Brian Griffin very much liked to take on a subject either in a serious fashion (in this vein, the reference to religious painting is familiar) or in a more absurd and satiric way, accentuated by Surrealism and the transposition of Socialist Realism in one of the biggest capitalist economies.

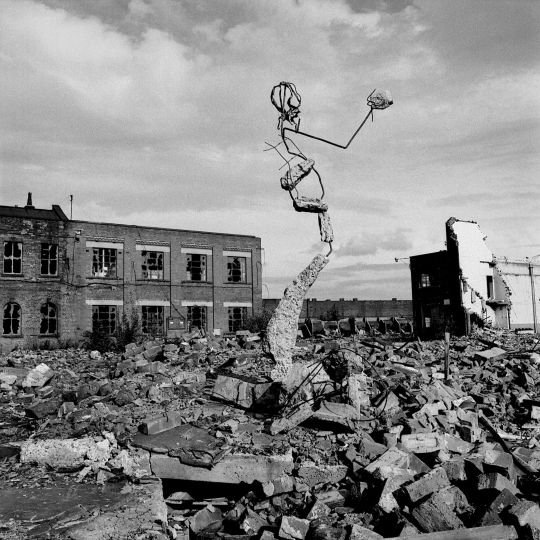

Having to deal with the working world in his assignments for magazines during the 1980s, Brian Griffin used these two references. The working class was magnified. In his 1986 series Workers, made in tribute to his deceased father, Brian Griffin made workmen pose lying down with their tools on their bodies, referencing knights’ graves in cathedrals. Conversely, white collared workers and bosses were armies of fighters. When the working class men were isolated most of the time, the business men were often in groups. At best, they were eccentric, at worst, distressing. 1987’s Bureaucracy made one undeniably think of a Kafkaesque universe just as much as Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil, two years earlier. With Brian Griffin, reality is always on the verge of science-fiction. In this recourse to dystopia, the photographer showed the nightmare of life under Thatcherism. Certainly, Brian Griffin took advantage of the money that was flowing which allowed companies to publish catalogues as beautiful as art books. Certainly, during that decade, companies transformed into fashionable places, making Brian Griffin a trendy photographer. And certainly, the dark suit became the cutting-edge garment worn by the new wave musicians of the time for whom, logically, Brian Griffin made numerous album covers. However, this new world was built upon the rubble of closed factories, the unemployed workers (if they had not died on construction sites). Brian Griffin had to learn of this class struggle by bitter experiences from his own life: a childhood spent growing up in the working class, of which he was very proud; an adulthood in the heart on the city of London during the 1980s amongst rock stars and characters much like those out of the mind of Bret Easton Ellis.

Anais Feyeux, Curatorial Director, Steven Kasher Gallery, New York City

EXPOSITION

Brian Griffin: Capitalist Realism

A voir également : Meryl Meisler

Du 25 février au 9 avril 2016

Steven Kasher Gallery

515 W. 26th St.

New York, NY 10001

Etats-Unis

Ouvert du mardi au samedi de 10h à 18h

http://www.stevenkasher.com

http://www.briangriffin.co.uk