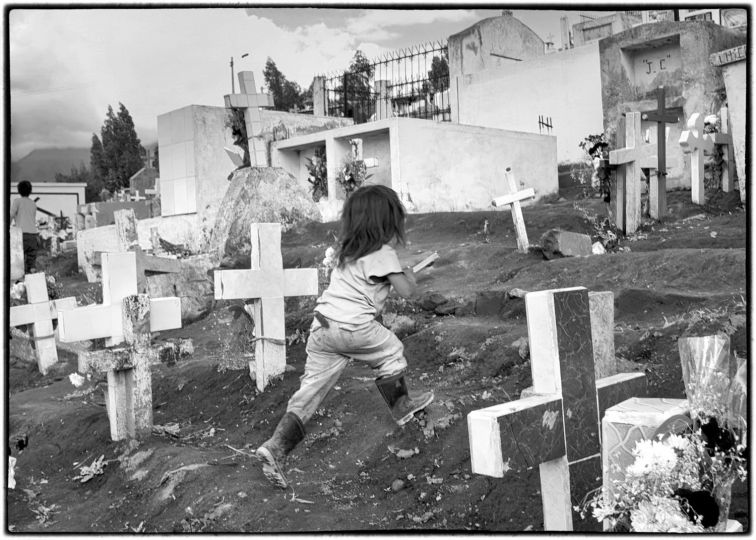

Acclaimed by the jury of the Hyères festival which noted his courage and honesty and awarded him the grand prix, the Irish Daragh Soden paints a halftone portrait of young Dubliners as they confront their uncertain future.

Teenagers flirting at the back of a bus or knocking around the beach in packs: they look like kids anywhere in the world, Berlin, Madrid, New York, or Tokyo. Soft colors and warm light almost mask the melancholy one can read in their eyes. There is a sense of boredom; afternoons spent in aimless wandering; unemployment waiting round the corner along with a bleak future. But let’s make no mistake. Life is bubbling up to the surface and demanding its due. Daragh Soden’s Ireland is not a country of EU subsidies, tax incentives vaunted by Google, or majestic landscapes advertised by travel agencies.

Soden’s photos speak of dashed hopes in a country where the ocean is always within reach while the multicultural youth are chained to their birthplace by widespread misery. The photos are about love, friendship, and ordeals, but also about being carefree. “My images reflect themes typically associated with youth: boredom, flirting, the sensation of being invincible one day and at the bottom of the world the next,” declared the young photographer, aged just 27.From his portraits emanate painful grace, poetic sensitivity, and desperate tenderness. Daragh Soden doesn’t wallow in pity, doesn’t judge, doesn’t stir up politics. His images reveal both a profound sense of humanity and the inexorable passage of time. “I wanted this series to be a celebration of youth, to capture its aura, to reflect its vulnerability as well as its strength, qualities that can be found in every generation, despite the passage of time,” he explained. We find the same trenchant examination of uncertainty about growing up in today’s Ireland in the very beautiful series by American photographer Doug Dubois, My Last Days at Seventeen, shot in Russell Heights, an economically disadvantaged neighborhood in Cobh, in the southwest corner of the country.

Soden’s teenagers, like Dubois’s, are floating in limbo. Caught up in the turmoil of often-painful metamorphosis, they are torn between a soothing sense of confidence and nagging self-doubt, between freedom and obstacles. The idea of existing in two worlds at once, portrayed with realism and subtlety, is the most sensible and probably the most accurate frame to convey the anguish of living in a society that is prey to chaos and intolerance. Whether cheerful or gloomy, these images of hard truth seem to tread a fine line between intimacy and detachment.

The two photographers deliberately blur the boundary between fiction and documentary in order to better reveal the complexity of the lives subjected to overwhelming forces. On the walls of the Villa de Noailles, next to his photographs, Daragh Soden wrote texts inspired by his own story and drawing on his memories to form a flowing storyline, like a voice narrating off-screen to fill in the gaps. Although he resides in London, the photographer has never forgotten his Dublin childhood. Born at the height of the economic boom, he saw his country slowly succumb to disillusion. Hit hard by the double financial and housing crisis, Ireland is ailing. The fierce “Celtic Tiger” of the early 2000s is a mere shadow of its former self. Young people were the first ones to leave, discouraged by a sluggish job market. Those who stayed behind face a future that has been emptied of meaning.

Working-class neighborhoods of northern Dublin have been overrun by gangs, drugs, and violence. This has taken a toll on daily life: the city has the highest firearm homicide rate in Europe. In a recent book, Ireland under Austerity, Michael Cronin, a professor in social science at the University of Dublin, points to the “endemic violence” generated by the recession in Irish society, and leading, among others, to an increased suicide rate, the second highest in Europe after Greece. Poverty, which had been only partly alleviated by reduced unemployment, is part of the daily reality in Ireland. This bleak picture is compounded by two major issues: emigration and geographic divisions. “I grew up in a booming, socially prosperous country,” says the photographer. “And then in 2008, everything took a nosedive. The country was engulfed in recession, public deficit went through the roof, businesses shut down, unemployment wreaked havoc on society. This period really shaped my identity. The young people I have photographed have only ever known the crisis and are going to pay for the errors of their parents. I felt it was essential that I pay a tribute to this generation by dedicating this series to them.”

Like Colin Barrett — whose short story collection, Young Skins, published in 2013, shed sobering light on Irish youth struggling, with hatred in their hearts, against a future they have already lost — Daragh Soden proves that even in the deepest darkness, one can find sparks of beauty. His images are an ode to tolerance, more needed than ever, even while narrow-minded parochialism is sweeping across Europe.

Cathy Remy

Cathy Rémy has been a journalist at Le Monde since 2008, where she features the work of young photographers and emerging visual artists. Since 2011, she has contributed to M Le Monde, Camera, and Aperture.