Casa Xochiquetzal is a shelter like no other in the world, a place where women find a home in old age after having lived on the streets as former—or current—sex workers.

The Mexico City house, with its open doors and easy-to-follow rules, offers shelter, food and comprehensive care at the same time it encourages community participation on the part of its residents. It is a shot at peace and dignity in old age, designed for a socially invisible segment. Its creation alone made manifest how few people—including the residents themselves—had ever stopped to think what happens when women in the sex industry grow old. The street, once their “showroom,” became their last resort as well.

First opened in February 2006, the shelter, located between downtown’s La Merced and Tepito districts, is a joint effort on the part of the Mexico City municipal government, which lends the building and provides food, and woman intellectuals and artists who, motivated by the case of one sex worker, created an NGO that receives donations from the public to provide the remaining necessities. This arrangement is what allows for Casa Xochiquetzal’s ongoing operation.

Over the life of the project—six years to date—more than 250 women have received support. While Casa Xochiquetzal began by admitting only women over sixty, it later became necessary to lower the minimum age; current residents number seventeen and range from ages 55 to 80.

Life at home became so restrictive for these women that they decided to make their way alone in the world. It wasn’t just men who ended up providing for them, though in some ways this was the case; they, too, were able to take care of themselves—back then.

Living under a single roof hasn’t been easy. Although many of the women knew one another for years on the streets, or from San Sebastián or San Fernando Plazas, they competed for clients. Yet little by little, coexistence has come to pass. One way of getting there was through workshops and activities, or establishing defined roles when it comes to cleaning the bathroom or making food. Everyone does something for everyone else and feels like she is part of a community. These are the women of Casa Xochiquetzal and Casa Xochiquetzal belongs to them.

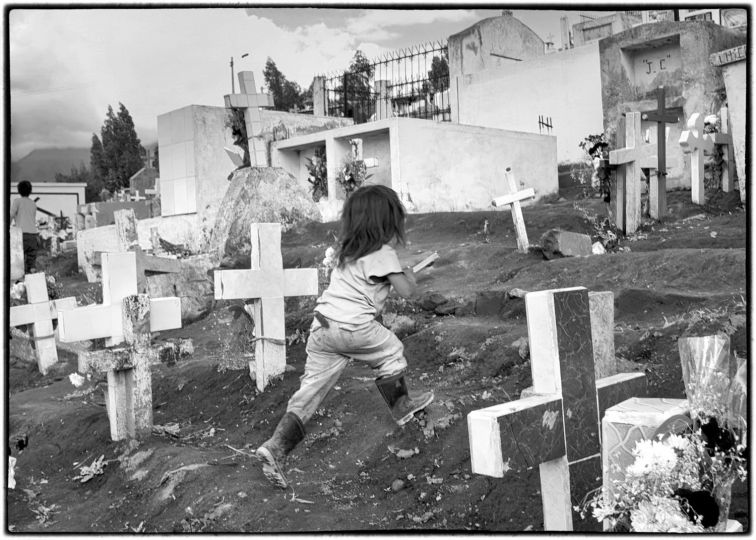

As part of our investigative journalism work over the course of more than five years, we have documented these women’s lives via eloquent visual representations. Later we talked to and interviewed them. We have gathered their stories; in many cases they begin with flight from childhood homes due to abuse on the part of parents, friends and sometimes even mothers. We have the women’s testimonies.

Sonia is from Sonora and is 62. Her family came to Mexico City and lived comfortably. Sonia liked parties and at one gathering, at age 14, she received a bullet wound in her head after being raped. Since then she hasn’t been able to move her left arm or leg much. But she turned to sex work anyway. She’s confident, loquacious, flirty and stylish.

Leticia watched, at eight, as her mother said goodbye to her from the back of a trailer, never to see her again. She is originally from Chihuahua. She worked at nightclubs and married. She didn’t walk out on her husband when he hit her—he made good money—but she did leave when he brought other women into their house. She abandoned everything, including her children. Two times she has tried to take her own life, yet she’s still here. She does yoga daily and tries to be a peacemaker and a good housemate. But her sweet expression can anger quickly. She knits, embroiders and always stays active; she likes reading the Bible.

Although she remembers being treated well at home, Norma was abused by one of her brothers when she was nine, and was also assaulted by the priest at El Refugio, Jalisco, where she lived. Soon after she decided to find work as a waitress in red-light districts, in a number of towns, because she always liked watching the dancers close up—“but not so close she’d get burnt,” as they used to say. She’s a cheerful woman, an extrovert, who’s got the dirt on everyone—absolutely everyone.

Canela is well known and respected in the neighborhoods that surround Casa Xochiquetzal. Originally from Oaxaca, she came to Mexico City to work at a very early age. At 72, she suffers from Down’s syndrome and a number of other illnesses. They say she liked to wear really short skirts, but today she sports them longer, or wears pants, when she goes out to peddle cigarettes and candy. She’s grumpy, but childlike, affectionate and kind at heart.

Marisol nearly finished her studies to be a teacher. She has Middle Eastern features but in fact is from Michoacán. She left home at nine, after a year in which her father “used her.” When she got to the Mexico City bus station, a runaway, she met a woman who sold tamales; the woman offered her a home and education. Marisol lost her at seventeen, when she died. She makes earrings and bracelets, embroiders, does a lot of reading and writes poetry.

Raquel, 66, is also from Michoacán, and came to Casa Xochiquetzal when it first opened its doors. She wears a wig and pads her bra. She is animated—words and songs come easily to her. She collects things. She has suffered from schizophrenia for 22 years and hears voices, but works hard not to lose touch with reality. She helps out selling clothes in a stand that her boyfriend of 31 years operates and also gathers plastic bottles for recycling as a way of earning a little money.

Of all the women, Canela was the only one not to have children. Most women who live at Casa Xochiquetzal have relatives, though in a number of cases, contact is sporadic or non- existent. None has ever contemplated an abortion and at times they are quite religious. Some have even attended burials of those who once tyrannized and demeaned them. They give limitlessly, and from the heart.

These are just barest fact about some of Xochiquetzal’s residents. Their belongings are few, but their memories are rich in detail. Theirs are stories of rage and of courage, that might seem like dramatic, often tragic, adventure. In spite of it all, they don’t give up. They all face the world proudly, and are dreamers, they still look for love, and in their generous life stories they show us the warrior spirit that lives inside them…perhaps until they draw their very last breath.

They’ve grown accustomed to being distrustful, to analyzing those around them. They are good storytellers, but more than that, born observers. Practical psychologists as well. They can act like fun, playful, sensitive little girls; or take things to extremes—they defend themselves ferociously at the least provocation. Fighting is their way of showing the world the claws they’ve needed to keep moving forward. They have a lot to teach us. Tough yesterday and still tough today, they maintain their dignity, body and soul.

Have you ever wondered what happens to sex workers when they grow old?

The result of six years of in-depth journalism, French Photographer Bénédicte Desrus and Mexican writer Celia Gómez Ramos’ new book, “Las amorosas más bravas” (“Tough Love”), presents intimate portraits of the women residing at Casa Xochiquetzal, a shelter for elderly sex workers in Mexico City.

Short preview of the book:

http://issuu.com/lasamorosasmasbravas/

To receive information or purchase the bilingual (spanish-english) book “Tough Love“, please contact at: [email protected].

Part of the sales of the book will be donated to the shelter “Casa Xochiquetzal”

Text by Celia Gómez Ramos

Photographs by Bénédicte Desrus

http://benedictedesrus.photoshelter.com